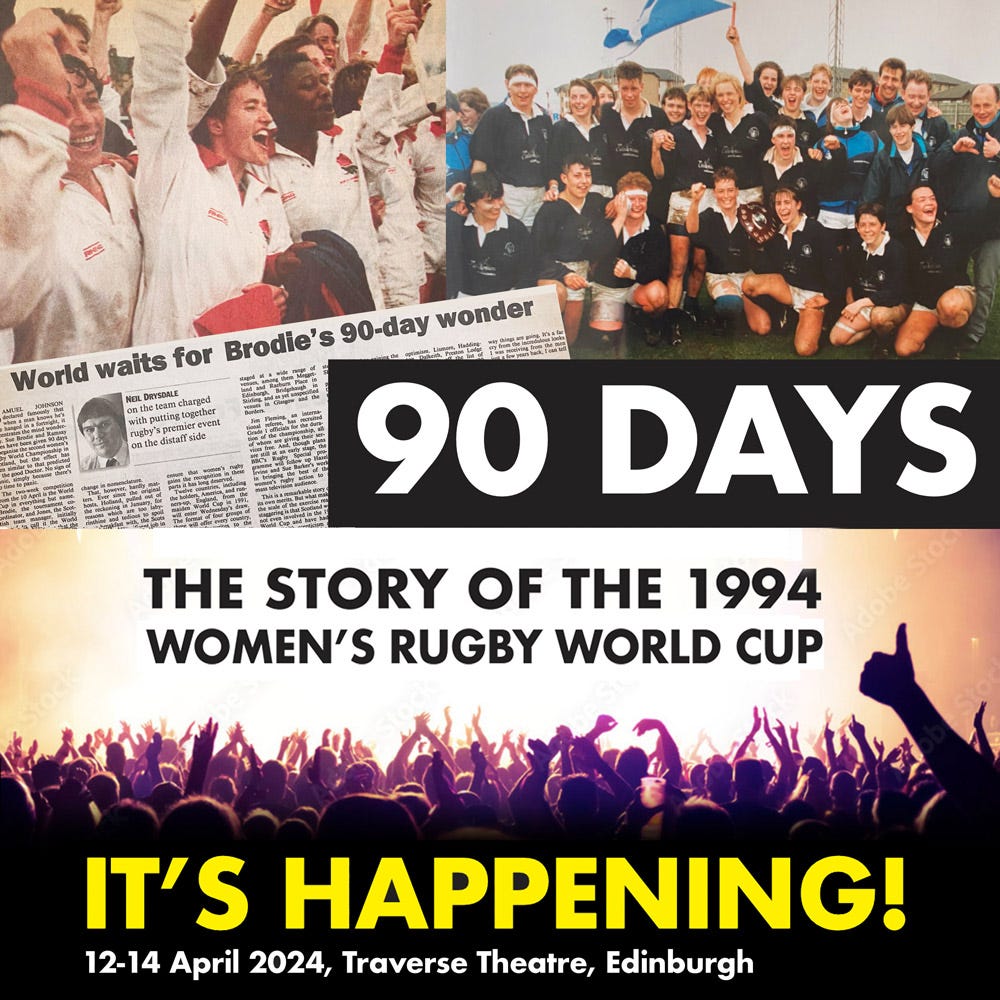

The women who saved the Rugby World Cup

The incredible Edinburgh team that changed sporting history - and inspired a stage play

Sue Brodie, Sandra Colamartino and their former teammates are Scottish sporting legends. Or at least they should be.

Their remarkable achievements are celebrated in the World Rugby Museum at Twickenham, have been the subject of serious academic study, and even inspired a stage play which debuts at the Traverse Theatre in April.

It is still entirely possible that you have never heard of them or the unlikely story of how they and their teammates saved the Rugby World Cup. They have not been feted in the same way as many other international players or the great pioneers of women’s football such as Rose Reilly. Yet their impact on their sport arguably puts them in the most select company in Scottish sport.

And, like many of the best Edinburgh stories, the story starts in the backroom of a pub in Leith.

They made it possible

Next year’s Rugby World Cup is already being billed as an “era-defining” tournament for the women’s game. When the two best teams on the planet walk out on to the Twickenham pitch for the final, it is likely to be in front of more than 60,000 screaming fans and broadcast live around the world.

The 2025 finals will be a showcase for the sport, taking in eight English cities and major venues such as Sunderland’s Stadium of Light. There will be replica shirts and blue chip sponsors. “The biggest, most accessible and most widely viewed,” according to World Rugby chairman Sir Bill Beaumont, "its unstoppable momentum will reach engage and inspire new audiences in ways that rugby events have not done before.”

Yet, it might not have been like this. Without the intervention of the Edinburgh players, it is doubtful the sport would be scaling the global heights that it is now.

First steps

Thirty years ago, women’s rugby was in its infancy in Scotland, largely the preserve of university students and a small, but passionate band of diehards.

Scotland had played their first match just the year before, beating Ireland 10-0 at Raeburn Place, home of Edinburgh Accies, in Stockbridge. Colamartino captained the side and scored both tries in the historic fixture.

Staging the game was an achievement in itself. Only a few years earlier, Sue had placed an advert in the Evening News in order to find the players to set up Edinburgh’s first women’s team.

Now, however, interest was building. The sport had momentum. It was an exciting time to be involved.

The next step was the World Cup. Three years after some of the Scottish players had attended the inaugural tournament in Cardiff as fans, they were preparing to play in the second version, having qualified for the finals in the Netherlands. The players were preparing for the ultimate sporting challenge, going head to head with the best in the world.

Then, disaster struck. A fax arrived in Brodie’s office in Edinburgh with a bolt from the blue. Three months before it was due to kick off, the World Cup was cancelled.

“It was devastating because it was everything that we were working towards,” recalls Brodie, who combined playing on the wing for the national team with chairing the Scottish Women’s Rugby Union and working as acting manager of Meadowbank Sports Centre. “There was no explanation. We didn't know why, it just wasn't happening. I was a player as well as an administrator, so I felt it from both those sides.

“I was emotionally upset, but I was also in a position to stop and think, right, what can we do?”

It would later transpire that bureaucratic hurdles placed in the way of getting the competition officially sanctioned by the game’s governing International Rugby Board ultimately put paid to the tournaments in the Netherlands.

An idea born in a bar

One day they might erect a blue plaque outside the Carriers Quarter, in Bernard Street, Leith, which was known as Todd’s Tap 30 years ago. It could read: “Inside this bar, in 1994, the Rugby World Cup was Saved.”

“It was the very beginning of January and after training a group of us went down to Todd’s Tap. It's got a back room which I thought would be a quiet place to go midweek.

“We went into the room and sat down. I just suddenly said ‘we could invite everybody and just have it here instead’. Well, in a way it wasn’t that suddenly, I had been thinking about it a lot.

“All we needed was an international tournament, people to play against. I was saying to them, how hard can it be, it's only a tournament - perhaps the most naive words ever spoken.”

What she was proposing was organising a Word Cup from scratch - inviting 16 international teams, staging 29 matches across two weeks in and around Edinburgh - with no money, no plan, no official endorsement, and only three months to do it.

There was only bemused silence at first from Brodie’s gathered teammates, as she calmly put the case that for teams already planning to travel to Amsterdam coming to Edinburgh was not that different.

Fueled by a burning sense of injustice, any initial scepticism quickly began to fade into the background.

Colamartino, then a 22-year-old scrum-half who was working as a graphic designer, recalls: “There was a feeling of being treated like second class citizens. If it had been the men's game, it would have been all over the news and ‘oh, what the disappointment for the men’, but this wasn't even a news item. We didn't debate it in any form. We were just thinking about what do we need to do to make it happen.”

The rest of the group came from all walks of life - software engineer Kim Littlejohn, lifeguard Alison Christie, teacher Micky Cove, police officer Elaine Black and Julie Taylor, a surveyor - all united by their love of rugby and a rare camaraderie.

Brodie, the rock of calm in the storm, adds: “The game in Scotland had such momentum and everybody was very motivated, there was such a spirit around it. It didn't take much convincing just to say, let's write to everybody and see if people want to come. If they want to come, then we'll do it.

“And that's what happened, the letter went out over the next day or two.”

Then, the replies started coming back.... from Japan, from Kazakhstan, from Canada and the United States. “The response was good. Good enough to stage a tournament.”

Some, including New Zealand’s Black Ferns, were unable to come. The unofficial nature of the competition meant some national governing bodies withdrew their support, financial and otherwise, or even forbade teams from travelling.

Most, however, were just delighted that the competition was back on. Crucially, the Scottish women’s team were unaffiliated to the Scottish Rugby Union at the time, so needed no one’s permission to press ahead with their plans.

So, an organising committee was formed, sponsors sought, grounds booked and money borrowed.

If you build it, they will come

“We had 90 days to do it, which is doable, but tight, yes,” Brodie recounts. “There was a lot of trust from the teams travelling that there was actually going to be something worth coming for. The Kazakhstan team, I've learned since, actually travelled to Edinburgh by bus. It took them three days to get here.”

By the time the players started arriving, the extraordinary efforts of the organisers had started to garner media attention. When problems arose, help came forward from various quarters. not gone unnoticed.

The Russian team arrived with nowhere to stay and no money, but with a large supply of bottles of vodka. The University of Edinburgh offered to put them up and Pizza Express sent pizzas every night.

‘Streams of people heading to the ground’

For Scotland’s final pool game at the Meggetland home of Boroughmuir Rugby, Scotland came face to face with ‘the Auld Enemy’ England.

“I was on the bench for that game. I remember we were warming up and just seeing these streams of people coming down from the main road down into the stand area. It was a Friday evening, the sun was shining, and I was just thought, oh, my goodness.”

Scotland acquitted themselves well, losing narrowly to the eventual champions in front of a highly enthusiastic crowd, and would go on to win the tournament’s Shield Final against Canada.

For the final, in which England’s Red Roses beat the United States, scaffolding stands had to be erected at Raeburn Place to accommodate the growing number of spectators. Around 1,000 showed up for Scotland’s first group game with Russia, while more than 5000 attended the final. A television crew came to capture the final action for BBC’s Grandstand.

Brodie remembers sitting up in the temporary stand with her teammates, a pint of beer in hand, surveying what was going on around her. “I don't think I really took in what was happening on the pitch. I was just sort of mesmerised by the response of the public to the game that we loved. It was amazing, a great feeling.”

Profit and legacy

Incredibly, the tournament in Edinburgh remains the only version of the finals to this day to turn a profit, allowing the organisers to repay the money they had borrowed to make it happen with a little left over.

Its legacy is far bigger than that. The tournament is widely credited with saving what was then the Women’s Rugby World Cup, ensuring its credibility as a competition and proving its popular potential as a sporting spectacle. Months after the final in Edinburgh, the International Rugby Board elected to officially support women’s rugby, encouraging member unions to integrate any women’s rugby organisations into their own structures.

The impact can also be seen on sports pitches across the city where more girls and women play the sport than ever before. Many, unbeknown to Sue, Sandra and their teammates, are there because they were inspired to pull on their boots by what they saw at Meggetland and Raeburn Place.

“We're getting these messages from people that had come to the games and said how inspiring it was and that their daughters in particular are now playing rugby,” says Sue. “You don't necessarily know about the impact at the time. It's been quite illuminating actually.”

Turning a crisis into a drama

Pretty much everyone who knew the story of how the World Cup was saved had said at one time or another ‘that would make a great film’. So, as the 30th anniversary of the tournament started to loom, Sandra Colamartino thought, why not? She signed up for an Edinburgh University screen-writing evening class and started the job of turning the events of 1994 into a script. “I knew if it had any chance of succeeding I had to have something that I could show people, it had to exist in some form.”

During a post-Covid cycling holiday in the Hebrides, Colamartino, who runs the artisan chocolate maker Quirky Chocolate, was struck by a moment of clarity.

“All we're trying to do is tell this story on the 30th anniversary, I thought I know exactly what we need to do. It needs to be a play. A bit like the World Cup, we don’t have to ask anyone for authorisation, we can make it happen - and who knows maybe Netflix can come along and want to make it into a film. It doesn't really matter.”

Sandra pulled together a rough draft and showed it to to the theatre producer and former President of the Scottish Rugby Union. They then commissioned playwright Kim Miller to write the script, who had the idea of turning it musical theatre. It was all made possible by a successful crowd-fund appeal.

For Brodie and Colamartino, that has meant seeing themselves as they were 30 years ago turned into characters in a play, whose story line carries inspiration for anyone who has found themselves excluded.

“My character really represents all the girls that never got a chance to play, then she experiences this sudden moment of seeing her dream come true,” says Colamartino. “We've got another character, Annie, for who playing for Scotland was a sort of journey of self discovery. Her story doesn't turn on a specific point of LGBT, but it is about when you find your tribe and where you fit in. It is through rugby that she finds that.”

Is it a bit like the Crown where fact and fiction blur in a way that famously makes the present King uncomfortable? “A little bit. Slightly alarming for the people that are in it, but equally if you let it go and count to 10, it's actually so funny. It's good to just not take the whole thing so seriously. You want people to laugh and giggle and and you've got to allow the writer to have some fun with the story.”

90 Days: The story of the 1994 Women’s Rugby World Cup takes to the stage for three nights at the Traverse Theatre, on 12-14 April, the same weekend that Scotland take on England’s Red Roses in Edinburgh in the Women’s Six Nations.

After that, who knows? A London run during next year’s Rugby World Cup seems too perfect to ignore. And what about that Netflix series?