The towering achievement of 'the Mick Jagger of the mountains'

Dougal Haston's extraordinary life returns to centre stage on 50th anniversary of the Edinburgh climber's Everest conquest

He must have thought it was a long way from climbing riverside embankments and railway walls in Currie. Dougal Haston stood atop the world - the distant horizon showing the curvature of the earth. It was a breath-taking, awe-inspiring, crowning moment.

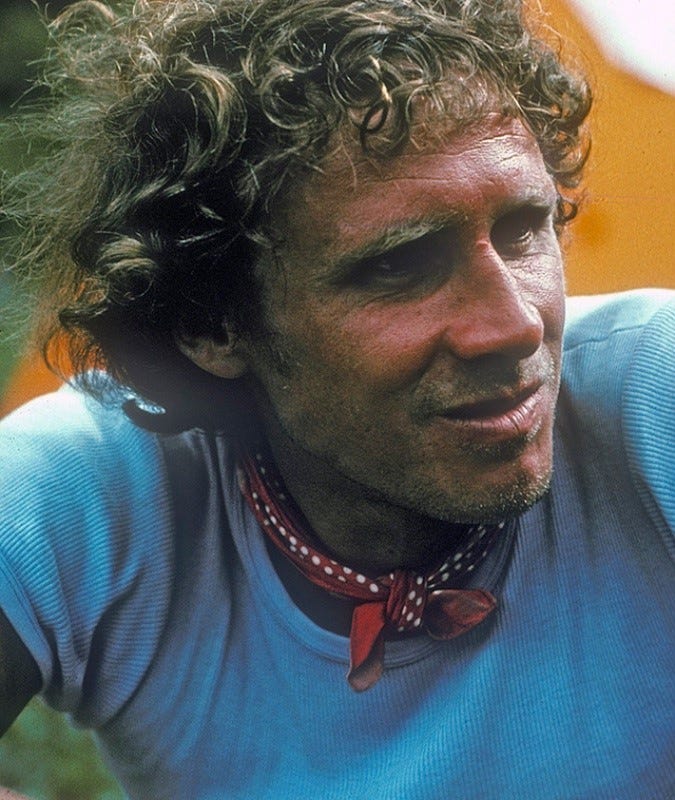

The Midlothian-born mountaineering legend, dubbed the “Mick Jagger of the Mountains”, had made the first ascent of Everest by a Briton, in lockstep with his friend Doug Scott.

It was September 24th, 1975, and the duo had also become the first climbers to reach the summit of the world’s highest mountain by its notorious south-west face, on an expedition led by Sir Chris Bonnington. It was the first time an ascent had been successful using a direct route up a face of the mountain.

Haston would say: “We were sampling a unique moment in our lives. Down and over into the brown plains of Tibet a purple shadow of Everest was projected for what must have been something like 200 miles. On these north and east sides there was a sense of wildness and remoteness, almost untouchability.”

Scott, who took the photograph above of Haston on the summit, said: “I was again a child; lost in wonder.”

Bonnington had hand-picked the duo to make the final ascent, writing in his book Everest - the Hard Way: “On Everest, in a talented bunch, they were head and shoulders above the rest.”

‘20ft leaps into the Water of Leith’

The towering achievement comes back into the spotlight in London on September 24th, fifty years to the day after the pair enjoyed their brief moments of wonder as they looked down on the world. A series of anniversary events will culminate at the Royal Geographical Society, in Kensington, London, with Bonnington and members of the 1975 team taking part in an evening of conversation, including film from the BBC coverage of the climb.

After the 1975 expedition, The Queen sent a telegram of congratulations to the 18-strong team for the “magnificent achievement.” It was a remarkable crescendo to a life and career that had its beginnings in Currie, with a group of boys using the high walls around railways and rivers to learn to climb.

Of those early days, Haston wrote in his autobiography In High Places that entry to West Calder High School had provided a further glimpse into the world of mountaineering through books. “It seemed another world but we kept on dreaming and practising on our railway walls. There was no money. Therefore no equipment. Six-inch nails for pitons and clothesline for rope. Very early discoveries as to the inadequacies of both. Stunning 20-foot leaps into the Water of Leith.”

This was no leap from sunny sea cliffs into an azure sea, as he would later experience. “Two paper mills and a tannery poured their refuse into it. One emerged scraped and stinking to limp home.”

Haston wrote: “Mountains have always exerted a strange influence on man. Grim and inaccessible, dwelling places of gods and spirits, they have always had an aura of the unknown and the mysterious. Mountain exploration is a relatively recent thing, and for many the old thoughts linger on. Perhaps that’s why mountaineers are thought to be oddities.

“But is it so odd to want a little adventure, to do a little exploration, to be a little individual in the over-organized mess? Even the most modest mountaineer achieves something when he takes his feet off the ground and launched upwards.”

Falling asleep would have brought death

A “little adventure” was something of an understatement. After they had reached the world’s highest summit in 1975, the sun began to set. It was becoming dark, and Scott and Haston had to move quickly. By the time they were just 300ft below the summit they realised they would have to make an unplanned stop for the night. They would need to survive without oxygen at 28,000 feet, the average altitude of commercial planes, in a snow cave they had to dig, and without food. They sat on their rucksacks, their down suits their protection against cold, and they fought sleep – to fall asleep would have been to die.

The next day they descended to safety, and two other members of the expedition reached the summit on the 26th. Tragically, BBC cameraman and climber Mick Burke who had been accompanying the expedition, struck out for the summit but never reappeared. Bad weather forced rescue efforts to be abandoned.

Haston had already become famous through his daring climbs, most notably on the Eiger. In 1966 he played a prominent role in the first direct ascent of the mountain’s notorious North Face, bringing international acclaim, after climbing through conditions Bonnington, who witnessed the climb first hand, described as “one of the most severe storms I have ever experienced in the Alps.” One climber died in the attempt, and a total of 21 toes were lost to frostbite amongst the team. Bonnington said: “It was in this Armageddon that Dougal emerged as the outstanding, self-confident climber that was to mark everything he did subsequently. It also marked the start of my own friendship with him.”

An advisor to Clint Eastwood

Haston’s prominence led to his being asked to assist in the making of Clint Eastwood’s “The Eiger Sanction” as a climbing consultant and safety officer.

He had gone from climbing walls to local rocks, to the mountains of Scotland, the Dolomites, and then on to the Alps, and the great Himalayas. He became a legend of mountaineering, one of the elite. Now he also rubbed shoulders with a Hollywood great.

His life did not always go smoothly. Most notably in April 1965, when he drove a transit van after drinking. In a terrible accident in Glencoe, he struck 18-year-old pedestrian James Orr, who died seven days later. Haston fled the scene initially but turned himself in within hours. He spent 60 days in Barlinnie prison, but the episode remained with him.

Indeed, Doug Scott – writing an appreciation in the Alpine Journal upon the death of his Everest companion in 1977 – said: “It often seemed that he pushed himself so hard in the mountains in an attempt to purge himself of the guilt he felt.”

After his climb on the Eiger, Haston had based himself in the Swiss Alps, where he had taken over the International School of Mountaineering at Leysin from his fellow-climber John Marlin, the climber who died on the Eiger. Dressed in his trademark polka-dot scarf, he worked and skied in Leysin where he was a regular at the famous Club Vagabond bar.

Haston’s death in 1977 was to provide an extraordinary end to a remarkable life. He had turned to writing, authoring a number of books, and had turned in the manuscript for his novel Calculated Risk. In the book, the hero Jack McDonald outruns a powder snow avalanche on La Riondaz, above Leysin.

Within days of handing in his handwritten book, Haston, an expert skier, himself went to ski La Riondaz, ignoring avalanche warnings. Scott said: “To ski down La Riondaz in such conditions was something that Dougal had long planned to do. He was obviously aware of the dangers as he set off… but triggered off an avalanche which overwhelmed him.”

His body was discovered under a few feet of snow the following day. He had been throttled by his scarf.

Haston was laid to rest in his beloved Alps at Leysin. A memorial stone stands in his native Currie, with a plaque recording his towering achievement.