The Science Festival: Edinburgh's other gift to the world

How the Capital created a concept that has helped changed the way we think

When Edinburgh decided to stage a public celebration of science in 1989, there was one problem. No one knew what a “science festival” looked like.

Unused to having its thunder stolen by Glasgow, who had just been awarded the European Capital of Culture for 1990, the Capital wanted to make a statement. How could it show that it was a modern, forward-looking city (despite all the talk of a city in stagnation and a centre dotted with gap sites and empty buildings)?

What better way than combining Edinburgh’s reputation as a festival city with its global prowess in scientific research and learning? But how to do that?

No one had ever staged a “science festival” before, anywhere in the world. The term was apparently first used by former Heriot-Watt University professor Ian Wall, then a member of the council’s economic development committee. It wasn’t that science events were unheard of in the 1980s, but they were aimed squarely at scientists, professional gatherings that didn’t open their doors to the public. They were about education not engaging the wider public, they were good for you, not fun.

An overnight hit

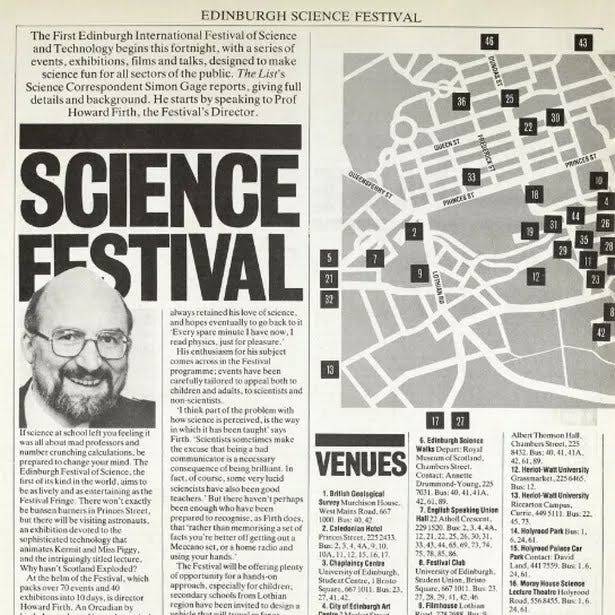

The Edinburgh International Festival of Science and Technology was an instant hit. The programme of more than 70 events and 40 exhibitions over 10 days - at venues including the City Arts Centre, the Edinburgh Filmhouse and Holyrood Park - would be recognisable to festival visitors today.

At a talk on the herbs of the island of Rum by the celebrated archaeologist Caroline Wickham-Jones the audience at the Botanics was served a sample of ancient beer, prepared by Heriot-Watt University researcher Geoff (now Sir Geoff) Palmer. The audience relaxed over beer, oatcakes and cheese - and loved it.

Simon Gage was the science correspondent at The List magazine at the time.

“I'm proud to say I was the List’s first science correspondent and Robin, who founded the magazine, asked me to write about Science Festival. I went to see events, interviewed people taking part and I thought it was amazing,” he recalls.

“It was very eclectic in the early days, there was a lot going on. Some of it was really wonderful and some of it was a bit rough at the edges, but it was a great invention. I could see that the start which is perhaps why I was so eager to go and work for them.”

The former research scientist joined the festival the following year - “basically as the tea boy” - and stayed for the next 34, the last 29 as chief executive and festival director.

A gift to the world

The Festivals are widely recognised as Edinburgh’s gift to the world, the pioneers without whom there would be no Fringe art festivals in Adelaide, Brighton, Montreal, Dublin or New York. The same is true of the science festival. It too has changed the world.

It’s success in connecting with audiences, blending everything from comedy to food and drink with science, was almost immediately recognised and copied. Today, there are thousands of such events around the world, all owing a debt to Edinburgh. The original remains one of the biggest and best.

“If you look at the TV scientist Brian Cox, he can fill the Playhouse and the tickets are not cheap. When was it last that a scientist could do that?” says Gage. “The whole inclusion of science and technology in culture has taken a leap forward. It's become much more acceptable now to do these things and enjoy these things than it was 30 or 35 years ago. We've had a hand in contributing to that, but there been many others at it.

“Science festivals and similar type of events have been testing beds for these new styles of presentation. They've been places where people like Brian and Richard Wiseman have had a chance to hone their craft. In the same way great comedians and actors hone their craft at the Fringe and get discovered, this festival network has been a benign place where these styles can be experimented with. Then, some go on and go big with the backing of TV which is the great amplifier of course.”

Always an innovator, the festival was an early pioneer in making science fun and accessible for children, deliberately moving events out of university and ‘scientific’ venues to visitor attractions and other places where more people felt more relaxed. Today, they continue to introduce people to “science by stealth”, selling 2000 tickets to late night parties at the National Museum and the Biscuit Factory, where visitors learned about mushrooms, foraging and the folklore of the plant.

A picture that changed everything

Over the years the Festival has investigated everything from the practical and ethical applications of AI to the joy, and pain, of Dad dancing.

It has welcomed many of the world’s most brilliant and inspiring scientists and science communicators. Notable among them have been David Attenborough (‘He gave such as stunning presentation in the McEwen Hall and had such charisma”); James Lovelock, the environmentalist and Gaia hypothesis theorist (‘He was in his late 80s when he came to the festival and still had a complete twinkle in his eye and razor sharp mind); and Christiana Figueres, one of the architects of the historic Paris Agreement on climate change (‘So determined, so gently persuasive and optimistic despite everything.’)

Alongside messages from scientists telling him that soldering their first circuit at the festival set them on the road to their career, Simon treasures some of the chance encounters he has experienced at the festival.

Sometimes that is simply watching the joy of a family making new discoveries at a hands-on event, other times it is meeting people who changed the world and our understanding of science.

At a dinner following one astronomy event, he found himself sitting next to a gentleman from the United States who had had not met before.

Simon asked the scientist what he had been working on to which he replied: “I ran the Hubble Space Telescope for a bit. “

“Fantastic,” said Simon. “Let me tell you the most impressive image I think I'm going to see in my life was the Hubble Ultra Deep Field image.

“I took that,” replied Robert Williams, the former director of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, describing one of the most revolutionary images in the history of science. “I had to fight for it. I ran the Hubble Space Telescope, but no one wanted me to do that. I insisted it was a good idea.”

Williams used the discretion he had as director over 10% of the use of the telescope to test what it would record by basically keeping it pointed at the dark sky for a very long time. The result was as profound as it was startling, literally exposing a previously unrecorded depth to the universe.

“The Hubble Space Telescope has made over 1.6 million observations since its launch in 1990, capturing stunning subjects such as the Eagle Nebula and producing data that is featured in almost 21,000 scientific papers,” Nasa states. “But no image has revolutionized the way we understand the universe as much as the Hubble Deep Field.

“Taken over the course of 10 days in 1995, the Hubble Deep Field captured roughly 3,000 distant galaxies varying in their stages of evolution.”

“It's just staggering what humanity is able to achieve,” muses Gage, “with instrumentation, deep thinking and calm analytical approaches. It's just, well, sometimes beyond belief.”

A powerhouse of science

The festival has very much been moulded by Edinburgh, forging lasting and rewarding relationships with a range of world class institutions, ranging from the Botanics and Museums of Scotland to the universities and the growing ranks of innovative start-ups. It has grown up and remains part of life at many venues such as Our Dynamic Earth, the City Arts Centre and Summerhall. The festival and the city is in many ways a match made in heaven, or perhaps in a research laboratory staffed by brilliant scientists.

“Edinburgh and Scotland have remained a powerhouse of innovation throughout the life of the festival,” says Gage with unbridled enthusiasm and a touch of pride.

“Britain's largest supercomputer is just outside Edinburgh and the Roslyn Institute which created Dolly the Sheep continues to do great work. The University of Edinburgh’s AI department, or informatics, as it's now called, was the second biggest in the world for decades. Some of the ground work was done here, and although it's dominated a little bit now by large corporations, the brains are still here.

“We're seeing great relations with the renewable energy industries because it's such a big part of the Scottish economy. Wave power. Wind power. Heat storage.

“It make running a Science Festival a whole lot easier because you're surrounded by people doing extraordinary things. If you’re going to give birth to a Science festival, this is one of the best plases to have done it.

“The research and development done in Edinburgh remains world class.”

What does Gage see as the next big thing, other than the obvious current obsession with AI?

“Who can tell? There's a substantial investment in robotics, there is a hotbed of innovation split between Heriot-Watt and the medical universities that produces incredible work. The expertise in climate change, and the use of land and the technology around climate change, is considerable here and is going to yield amazing things.”

What is next?

As Gage prepares to step down from his role as Festival director after almost three decades, he sees a bright future for one of the city’s best-loved institutions.

“Technology is moving at such a pace it will remain intriguing and important for everybody. There's never a shortage of material to talk about, to object to or to want to know more about.”

After a working lifetime in science, it is not surprising that Gage has a clear idea of his next priority - or the nature of that priority.

“I'm going to go and do something in the area of climate change. It has become so urgent for me that I can't not do it. I don't know what that will be yet, but with the energy I've got left, I think that has to become my priority.

“The thing that has to happen is we have to have to deal with climate change. The rest is all nice, but if you don't deal with climate change, then we’re in a mess.

“I will be aiming to work with non-specialist audiences to try to persuade people - engage them with a change that has to come, accelerate it - because time is running out a bit for the planet.”

The Edinburgh Science Festival 2024 ends tomorrow

Opening up the world of the workshop

When the creative team behind theatre and events sets for many of the Capital’s festivals and venues struggled to find suitable workshop facilities, they decided to do something about it.

Stuart Nairn, Natasha Lee-Walsh and Nicola Milazzo identified a vast former 19th century coachworks in Leith and - armed with a Transmit business start-up loan - set about creating the Edinburgh Open Workshop (EOW).

The open access workshops for artists and creators threw open their doors in July, 2018, providing fully-equipped facilities for professionals and amateurs alike.

Home to wood-turners, welders, upholsters and theatre production designers, the only facility of its kind in the Capital now has a community of 18 full-time resident makers and 300 pay-as-you-go members.

The three founders, working as Big House Events, have created everything from giant books for International Book Festival visitors to enjoy and a giant beer can for Still Game’s farewell live show at the Hydro through to complete theatrical sets for festival shows and the Traverse Theatre.

EOW is a social enterprise so all profits go back into improving the equipment and support available. It has grown over the last six years and with the increase in interest in crafting and DIY developed a range of more than 20 courses and workshops.

Having previously hosted makers’ markets and other community events, EOW is holding its first family fun day at 39-41 Assembly Street, Leith, on Saturday, 27 April, at 10am-4pm, with free entry, including tours and taster sessions in cane weaving, planter making and woodturning.

Co-director Natasha Lee-Walsh said: “This is our first ever family fun day and we can’t wait to welcome members of the public to the Edinburgh Open Workshop and show them what we do here.

“EOW provides professional makers, students and DIY enthusiasts with training, support and a flexible, fully equipped place to work. We are delighted to be opening our doors and inviting local residents to join our community of artists and crafting professionals, show off our amazing facilities and specialist equipment, and inspire visitors of all ages to try something new.”