The Leith-built ship of hope that steered to the first Blue Riband

The men and ship that made history in daring trans-Atlantic race against Brunel's mighty Great Western

Ahoy there! All ship shape, and ready for a voyage of discovery? Shall we take a little time this weekend to chart waters little known?

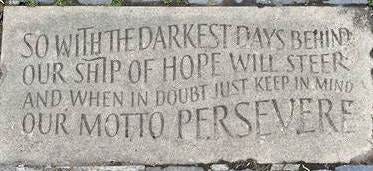

This is a story of pioneers, of ambition, of competition, of victory. Ultimately there’s tragedy in there too. But, really, at its most basic it’s a “tortoise and hare” tale of perseverance – appropriate for a story that has its earliest beginnings in Leith. Persevere is, after all, the port’s motto.

There’s a good tot of Hollywood glamour to help our tale along, full of swashbuckling and swooning on the high seas and an onscreen appearance of that most enduring of characters, the Scottish engineer. Aye, aye Cap’n.

Ready to cast off shipmates? Excellent, then let’s weigh anchor and set full steam ahead for the story of a Leith-built ship that made headlines around the world less than 200 years ago. I know, I know, we’re hardly breaking the news here but it’s a grand story. And I promise to keep the jaunty nautical terminology under control from here on.

Leith, you will know if you are of a certain vintage, was once a place where ships were built. Men had been toiling to create ships for hundreds of years in Leith before anything sailed from the yards of the Clyde.

Even a King’s flagship. The Great Michael, built for James IV as part of his policy of constructing a strong Scottish navy, was launched in 1512 and could carry 300 sailors, 120 gunners and 1000 marines in her 240ft long hull. In her day, she was the largest ship afloat.

Ships continued to be built in Leith right up until the 1980s, through the nationalisation of the myriad shipyards as decline set in, when Henry Robb’s (then Robb Caledon) closed its gates for good despite industrial and political campaigns to keep it open.

However, we’re in danger of drifting. Back to our course, which begins in one of the Port’s oldest yards, run by the Menzies family from the middle 1700s. Wooden ships were the thing, sailing ships, the great wooden ribs of their hull a common sight as the yards went about their craft. Robert Menzies & Son were steadfast in building the Leith ship industry, but they were about to become pioneers in changing it.

Wind had powered ships across the seas for centuries, but steam was the coming thing. Modern, reliable, and fast. But could it cover the really big distances – after all, there was only so much coal a boat could carry. Enter Leith’s shipbuilders and the SS Sirius.

In 1837, Menzies built the side-paddle steamship that would be named SS Sirius for the St George Steam Packet Company at a cost of £27,000. It was made of wood and measured 178 feet and four inches long, and she had a gross tonnage of 703 tons.

For the Top Gear types among you, the two-cylinder steam engine made by Wingate & Co of London drove two paddle wheels that delivered 380 horsepower and gave a maximum speed of 12 knots. She was built to be a coastal steamer, transporting cargo and passengers on the Cork-London route.

At the time Sirius was built in Leith, shipping companies were in fierce competition to see who would be first to travel by steam power only all the way from Europe to North America across the Atlantic Ocean – no-one referred to it as “the pond” in those days. Another steamer, the SS Savannah, had made a trans-Atlantic trip from the US to Liverpool, but had used sail for large parts of the journey. The entire distance under steam was still to be achieved. Fate was about to step in for the SS Sirius.

The grandly named British Queen, was ready for its trans-Atlantic tilt in 1938 and its owners, the British and American Steam Navigation Company, decided to charter the nimble but possibly under-sized Sirius to make the run to New York instead.

There would be competition, of course. The iron-hulled SS Great Western was designed by probably the most famous engineer in the world, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and owned by England’s Great Western Steam Ship Company. What is more, it was the first steamship specifically built to cross the Atlantic Ocean. Bigger, at 1320 tons and 212 ft long.

On 4 April 1838, the Sirius left Cork under the command of local man Richard Roberts, who had served with distinction in the Royal Navy as a Lieutenant. The vessel was cheered on by thousands of well-wishers as she made her way out of harbour. She was carrying 40 passengers, 450 tons of coal, 20 tons of water and cargo, including casks of Stout.

On 31 March 31, the Great Western had begun her historic maiden voyage across the Atlantic by sailing to her starting point of Bristol. On the way a fire broke out in the ship’s engine room and – in the confusion – Brunel suffered a fall of 20ft and had to be put ashore injured. The ship’s departure was delayed until 8 April as a result, and in addition more than 50 people cancelled their bookings on the ship. When she did set off, she carried only seven passengers.

But Brunel’s ship was faster, and they were confident of overhauling their unexpected rival. They almost did. The Sirius, built for shorter trips, had burned all its coal, and looked in danger of falling agonisingly short. But the captain, Roberts, refused to raise sails and instead ordered everything possible burned to fuel the engines - including furniture and reportedly one mast and spars - in his determination that Sirius would enter New York Harbour as winner.

And she did - some 18 days, four hours and 22 minutes after leaving Cork. She wasn’t the largest or the quickest, but Sirius and Roberts had persevered. The tortoise won the race. The captain and crew of 38 were feted. The Leith-built ship had captured the public imagination on two continents. American newspapers were enthralled by the ship and her accomplishment.

Aaron Clark, the mayor of New York, and representatives of the US army and navy all made visits to the ship, and in recognition of his achievement, Richard Roberts was awarded the freedom of New York City. Both Cork and London also awarded him the freedom of their cities.

The Great Western arrived the following day, to far less celebration. In the Big Apple, some things never change – first is first and second is nowhere. Even so, the Great Western had made the journey in fewer days and was to go on to make the trans-Atlantic crossing many more times, earning considerable fame in the process.

Nonetheless, Sirius was first to cover the distance entirely under steam and was truly the first winner of the coveted Blue Riband. However, our story doesn’t end there. The story of the race to steam across the Atlantic inspired a Hollywood movie. Paramount’s 1939 release “Rulers of the Sea” was based partly on the Sirius, the movie ship even being called “The Dog Star” (Sirius is in the Canis Major constellation, and is often referred to as the dog star). Stars were Douglas Fairbanks Jnr, Margaret Lockwood and a young Alan Ladd.

The move also featured Will Fyffe as John Shaw, a Scottish engineer and inventor of a steam powered ship. Fyffe was already a star in the UK, particularly after penning the song “I belong to Glasgow”.

In February 1841, Richard Roberts commanded another steamship, SS President, as it crossed the Atlantic for New York, beginning the return journey in March. He had been concerned the ship was not seaworthy, and in this he proved tragically correct.

A naval officer who had been wounded in action tackling slavers, he had privately expressed concern that the President was not seaworthy and he was sadly correct. It disappeared, was never seen again, and it was clear she had sunk in mid Atlantic during a storm. Roberts, his crew, and the passengers aboard all drowned.

The Sirius fared no better. After one more trans-Atlantic trip she returned to the UK-Ireland routes, and, on January 16th, 1847, was travelling from Glasgow to Cork via Dublin with 90 crew and passengers on board when she hit a reef in dense fog and was wrecked in Ballycotton Bay. Most of the passengers were rescued, but 20 lives were lost in the heavy seas, most when an overloaded lifeboat was swamped. Sirius was carrying casks of Guinness, and it is said that locals were looting the ship and pillaging the casks.

At the time, the London Daily News reported: “Meanwhile, the steamer continued to thump heavily on the rocks, while the screams of alarm from the affrighted passengers, and the heavy surf breaking on her sides and on the deck, rendered the scene one of awful danger and intense anxiety.

“Soon after, the Coast Guard boat from Ballycotton station, under command of Mr. Coghlan chief officer, came alongside and the ship's boats, having by this time been also launched, the remaining passengers were got into them and safely landed, though with the loss of every portion of their luggage.

“We are sorry to learn that the country people in that wild and wretched locality availed themselves of the melancholy occasion to carry off everything they could lay their hands on. Every article that was washed ashore before the assistance of military or police arrived, was instantly carried off.”

Sadly, our tale also ends tragically for two of the main players. But one notable piece of the Sirius remains at Hull Maritime Museum - rescued from the wreckage. The figurehead from the ship, a dog holding a star in its mouth.