The Edinburgh man who accepted Napoleon's surrender

And the story which owes its publication to the intervention of Sir Walter Scott

It was a calm Saturday morning, 15th July 1815, and at the break of day Captain Frederick Lewis Maitland was told a French brig’o war was standing off his ship of the line, flying a flag of truce.

On the quarter deck Captain Maitland, born in Fife but educated and brought up in Edinburgh, kept his excitement in check. The reason his heart beat a little quicker that day was about to become clear as he sent the ship’s barge to the French ship to collect his Very Important Passenger.

The arrangements had been agreed in delicate discussions over several days. The appearance of the French ship had confirmed those arrangements. Maitland was about to accept the surrender of the greatest general in military history. But you would never detect his anticipation from his entry in the ship’s log that day.

One stark, simple sentence stands out in summary of a moment of huge historical significance: “Received on board, Napoleon Buonaparte (sic), late Emperor of France.”

As Captain of HMS Bellerophon, he led three ships engaged in a blockade of the French ports near Rochefort, seeking to ensure the man known affectionately to his devoted soldiers as The Little Corporal did not slip out to sea to make good his desired escape to North America.

Maitland was to spend much time with Napoleon, engaging in conversations about military and naval tactics and a multitude of other topics in the Captain’s cabin, which he gave over to Napoleon for the weeks the Emperor was on board. The Emperor’s entourage, described as his “suite,” was also suitably accommodated as guests of the Royal Navy.

While it would be an episode that wrote Maitland’s name into history, it was also to become one that unfairly called his integrity into question, causing him to publish his own detailed account. It certainly helped - his reputation remained unsullied and he eventually rose to the rank of Rear Admiral and received a Knighthood.

Maitland had agreed to take Napoleon to England. A warrant for the former Emperor’s arrest had been issued by the newly-restored constitutional French monarchy of King Louis XVIII.

Captain Maitland, from a distinguished military family, tells us in his own detailed account, The Surrender of Napoleon, what happened when the man who had conquered vast territories of Europe came on board: “He came on the quarter-deck, pulled off his hat, and, addressing me in a firm tone of voice, said, ‘I am come to throw myself on the protection of your Prince and laws.’”

“the difference of 40,000 men”

The Prince was George, son of King George III, who was the British monarch at the time, but whose declining mental health had seen his son take on the role of Prince Regent. Napoleon had written to the Prince explaining that he hoped to live in peace in England.

It was to be the start of the short, but eventful, relationship between the courageous naval officer, and the man who had won a staggering 38 of the 43 battles he fought.

Just a few months earlier, he had been decisively defeated by the Duke of Wellington and his allies at the Battle of Waterloo. Wellington had often maintained Napoleon’s “presence on the field made the difference of 40,000 men.”

Napoleon did not pass any view on his great nemesis, the Iron Duke, directly to Maitland. However, in his account Maitland says: “I asked General Bertrand what Napoleon thought of him. Why, replied he, I will give you his opinion nearly in the words he delivered it to me. 'The Duke of Wellington, in the management of an army, is fully equal to myself, with the advantage of possessing more prudence.'"

Maitland was also keen to dispel rumours that Napoleon had behaved badly on board his ship, or that he had bullied members of his entourage. Indeed, Maitland said of him: “His manners were extremely pleasing and affable: he joined in every conversation, related numerous anecdotes, and endeavoured, in every way, to promote good humour: he even admitted his attendants to great familiarity; and I saw one or two instances of their contradicting him in the most direct terms, though they generally treated him with much respect. He possessed, to a wonderful degree, a facility in making a favourable impression upon those with whom he entered into conversation.”

Things, however, were to sour in terms of Napoleon’s view of the British as the “most generous” of his enemies. He had wished to live in England, purchasing a small estate, and indeed that had been the subject of his letter to the Prince Regent.

But whilst the Bellerophon had spent more than a week at sea on its journey to England, and while it then lay at anchor first at Torbay and then Plymouth for a number of weeks, the British Government had been deciding how to deal with the former Emperor. And their decision, to send him to Saint Helena in the remote South Atlantic as a prisoner of war did not sit well with him.

Napoleon’s protest

He wrote in protest: “I hereby solemnly protest, in the face of Heaven and of men, against the violence done me... I came voluntarily on board of the Bellerophon; I am not a prisoner, I am the guest of England. I came on board even at the instigation of the Captain, who told me he had orders from the Government to receive me and my suite, and conduct me to England, if agreeable to me. I presented myself with good faith to put myself under the protection of the English laws. As soon as I was on board the Bellerophon, I was under shelter of the British people.

"If the Government, in giving orders to the Captain of the Bellerophon to receive me as well as my suite, only intended to lay a snare for me, it has forfeited its honour and disgraced its flag. If this act be consummated, the English will in vain boast to Europe of their integrity, their laws, and their liberty. British good faith will be lost in the hospitality of the Bellerophon.”

Maitland then had questions to answer to the Admiralty, but his meticulous record-keeping, his wisdom in ensuring witnesses were present to almost all conversations, were to prove invaluable. His own account set the record straight, proving he had specifically cautioned Napoleon’s advisers that he was not authorised to make any promises of how the British Government might view the Emperor’s situation, which was backed by at least two other senior officers who had been witness to conversations. Such testimony also cleared the British Government.

Despite the contents of his letter of protest, Napoleon did not seem to share the view it evinced of Maitland. Indeed, shortly before leaving to transfer to the ship which was to transport him to the South Atlantic, Napoleon sent for the Captain. Maitland reports: "On the morning he removed from the Bellerophon to the Northumberland, he sent for me again, and said, 'I have sent for you to express my gratitude for your conduct to me, while I have been on board the ship you command. My reception in England has been very different from what I expected; but you throughout have behaved like a man of honour; and I request you will accept my thanks, as well as convey them to the officers, and ship's company of the Bellerophon’.”

Maitland was keen to know how the Emperor’s stay had been viewed by the crew, and asked one of his men. who replied that he had heard several of the crew conversing that morning and added “One said, 'Well, they may abuse that man as much as they please; but if the people of England knew him as well as we do, they would not hurt a hair of his head;' in which the others agreed."

Napoleon never set foot on British soil.

Scott’s support

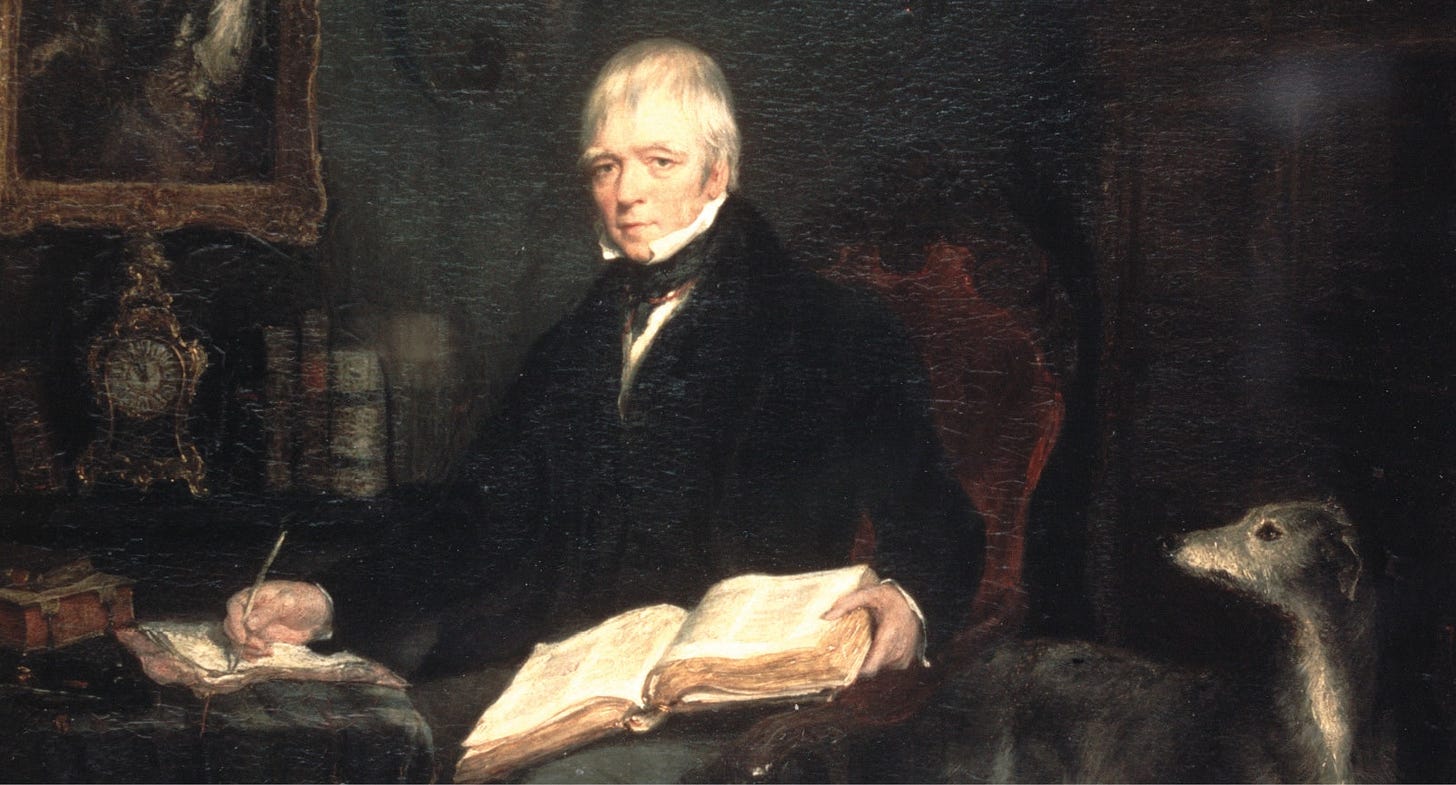

It’s a fascinating story of enormous historical significance, yet had fellow Edinburgher and literary great Sir Walter Scott not encouraged Captain Maitland not only to publish his tale, but to ensure it was not cut and altered in the telling, then the full account may never have come to light. Lost to time. By coincidence, both men had been pupils at the city’s Royal High School, but a few years separated their time there.

By his own admission, Maitland had “thrown together” his notes on the historic episode for friends alone to read, but subsequent events - and the accusations levelled against his character - persuaded him to consider wider publication. At that stage his writings were sent to Scott, who replied saying:

“The whole narrative is as fine, manly, and explicit an account as ever was given of so interesting a transaction. It is one in which Captain Maitland not only vindicates his own character, but guarantees that of the British nation. I really, since an opportunity is given me by Capt. Maitland's confidence, protest against its being snipped and clipped like the feet of the ladies who wished to qualify themselves for the glass slipper.”