'The Cockburn has a reputation for saying no, but honestly it's not deserved'

Conservation charity's new director on a bad rap, supporting ambition, and the problem with Waverley Station

A ‘motorway’ cutting through the heart of Edinburgh and a giant roundabout in the heart of the West End. A towering high-rise the height of Edinburgh Castle at Haymarket and the public barred from Princes Street Gardens .

Some of the failed schemes for developing the Capital over the years seem extraordinary to our modern sensibilities, but Edinburgh might be a very different place today if the city’s civic trust had not weighed in against them.

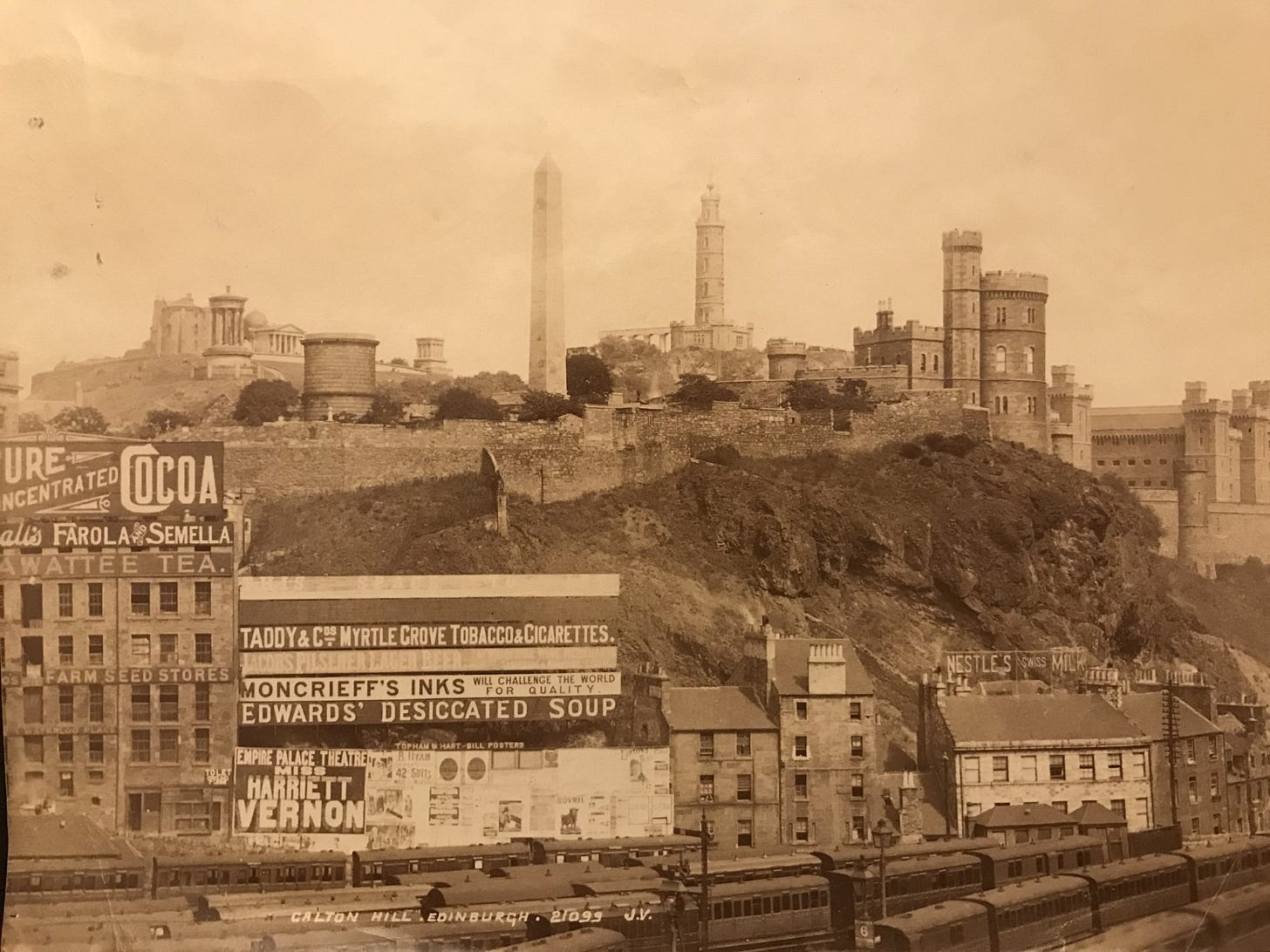

The Cockburn Association was founded in 1875 to promote and encourage the care and conservation of Edinburgh’s unique architectural and landscape heritage. Named after Henry Cockburn, a Scottish legal and literary figure born in the 1700s, it is Scotland’s oldest conservation body.

Generations of volunteers have given their time and energy to prevent inappropriate development in Edinburgh – everything from elevated motorways and destruction of the Old Town to intrusive advertising and so-called over-tourism.

On many occasions, it has been ahead of its times. One of its first campaigns, just a year after its inauguration, was battling for public access to Princes Street Gardens. The green space had recently been created on the drained site of the former Nor Loch – notorious as a stinking cesspit where much of the city’s waste, and worse, ended up - but was not always open to all.

In the same year, the trust began campaigning against the felling of mature trees to make way for development and pushing the city council to replace chopped trees with new planting. Concerns over the environment – namely the choking smoke and smog which earned the city its Auld Reekie nickname – were first raised as early as 1880, sparking a campaign to improve conditions.

Other notable interventions include pushing for various Scottish government buildings to be brought together, resulting in the erection of art deco masterpiece St Andrews House in the 1930s. It also campaigned to protect beaches – and local children – at Cramond and Granton from industrial waste dumped by the nearby gas works.

It didn’t always get things right. It famously objected to the building of the Balmoral Hotel, now considered one of the city’s architectural treasures, when plans were first put forward at the turn of the 20th century.

Now, 175 years on, the charity has a new leader. Rowan Brown took up the reins as director late last year, taking over from Terry Levinthal, who held the post from 2017. She is dedicated to continuing the ethos of the Cockburn Association’s historical work, looking “to ensure that Edinburgh is a city fit for the future, and respectful of its past”.

A passion for progress

A relative youngster at 44 years old, Brown brings considerable energy and passion to the role, drawing inspiration from her upbringing, life experience and previous jobs in the museum sector. With a Glasgow mother and Edinburgh father, she has a foot in each of Scotland’s biggest cities and often compares how they have been developed over the centuries. An architect grandfather was also a big influence on her career path, which kicked off with a course in art and architectural history at the University of St Andrews when she was only 16.

With first-hand knowledge of mobility challenges, she is a strong advocate for solutions to improve accessibility and is especially committed to safeguarding nature. As well as preserving historical buildings, she believes in sympathetic and well-designed modern constructions and refurbishments. And her enthusiasm is palpable.

“Things shouldn’t just stagnate or be preserved in aspic. It doesn’t do anybody any good,” she says. “I’m particularly passionate about accessibility from an ability perspective. I’m a disabled person myself and it really matters to me. For example, since Waverley stations became pedestrian-only, it’s a real challenge for people to get in and out of the city. And that’s a problem, I think, in Scotland’s capital.

“I’m also really devoted to preserving nature, access to nature and green spaces, and supporting ecosystems. A lot of my work has been on those themes over the last 20-plus years. And I think Edinburgh, inevitably, with its ancient heart, has a particular challenge with physical accessibility and intellectual accessibility just because of the masses of people.”

Edinburgh today

Current projects under scrutiny include the proposed extension to Edinburgh’s tramline, the revitalisation of Princes Street and plans to demolish the Brutalist Argyle House at the foot of the Castle Rock to make way for a new development.

The charity is concerned that the case has not yet been clearly made to justify the up to almost £3 billion cost and massive disruption that the proposed north-south tramline would bring. It advocates for “breathing new purpose” into buildings like Argyle House, with its large, angular, concrete edifice, which split opinion like Marmite, rather than demolishing them.

It is also worried about Princes Street, warning that: “Poorly handled, Princes Street risks becoming a diluted stage set for transient retail cycles and short-term commercial expediency. With imagination and leadership, however, it could reassert itself as a coherent, distinctive and genuinely civic boulevard.”

Stuck in the past