Still radical after 100 years: Edinburgh’s most influential forgotten thinker

Patrick Geddes, his ‘thinking machines’ and saving the Old Town

Sandwiched between two tourist shops at the top of the Royal Mile is the opening of Riddle’s Close.

Like many of the Old Town closes, it is low, narrow and dark. This close, though, leads to a time machine of a building. In its 500 years of existence, Riddle’s Court has been everything from a grand residence housing Lords and hosting Kings, to a slum for nearly 200 people, to Edinburgh University’s first student residence.

Now, nestled in a well-preserved historic Old Town, Riddle’s Court is a tribute to one of the people responsible for the Old Town’s transformation.

Patrick Geddes may be well known to aficionados of Edinburgh history, but he has been largely forgotten by the wider world. You may not have heard of him, but his influence is everywhere.

His principle of “conservative surgery” ensured that, in the late 19th century, the most important parts of the Old Town were conserved, while the dilapidated slum was transformed to accommodate modern living. He was involved in the rebuilding of Riddle’s Court, the design of Ramsay Garden, the creation of greenspaces all over the Old Town, and led efforts to repair, improve and revitalise many other buildings.

“The history of Geddes in Edinburgh was quite profound, and people don’t always appreciate that,” says Samuel Gallacher, Director of Scottish Historic Buildings Trust. Gallacher will be speaking at a celebration of Patrick Geddes’ life on Saturday, as part of the Edinburgh 900 festivities.

Who was Patrick Geddes?

Born in Ballater in 1854, Geddes arrived in Edinburgh in 1884 after extensive travels from London and Paris to Naples and Mexico. While Geddes was not native to Edinburgh, he was fascinated by the city. The Old Town, built on and constrained by the crag and tail formation on Castle rock, was the perfect example of a human settlement completely intertwined with its natural environment.

With a day job at the Botanic Gardens, Geddes was passionate about revitalizing the Old Town, which had become a slum in the wake of the upper and middle class exodus to the New Town. A believer in change from within, Geddes moved himself and his family to the heart of the Old Town, and much of his work focused on bringing professionals back into the south of the city.

The power of leaves

Geddes’ approach to urban redevelopment was revolutionary. With a background in ecology and botany, and a desire to improve the lives of human beings, Geddes was one of the first to see urban spaces as ecosystems. “He understood that from a botanical sense a plant would need different elements to be healthy and grow well. And human beings also need different elements, and the space to be in was so important to that- light and air in particular,” said Gallacher.

Green space was also an important part of Geddes' idea of a healthy space. 'How many people think twice about a leaf? Yet the leaf is the chief product and phenomenon of Life: this is a green world, with animals comparatively few and small, and all dependent upon the leaves,' said Geddes.

Understanding that the social environment was important to creating a liveable city, Geddes founded the Edinburgh Social Union of landlords who committed a proportion of their old town rents to building maintenance and improvement for tenants.

The Edinburgh Social Union was a vessel for putting Geddes theories into a practice en masse. “It was a way to take what had been this beautiful incredible historic city centre, that had become so abandoned and become dangerous and dirty and unhealthy and transform it,” said Gallacher.

Thinking machines

Geddes didn’t just change what Edinburgh looks like. He changed the way decisions were made. Despite his obvious talent, Geddes seemed to have little patience for formal exams and educational institutions; he never completed his degree at Edinburgh University, and he spent most of his career outside traditional academic circles.

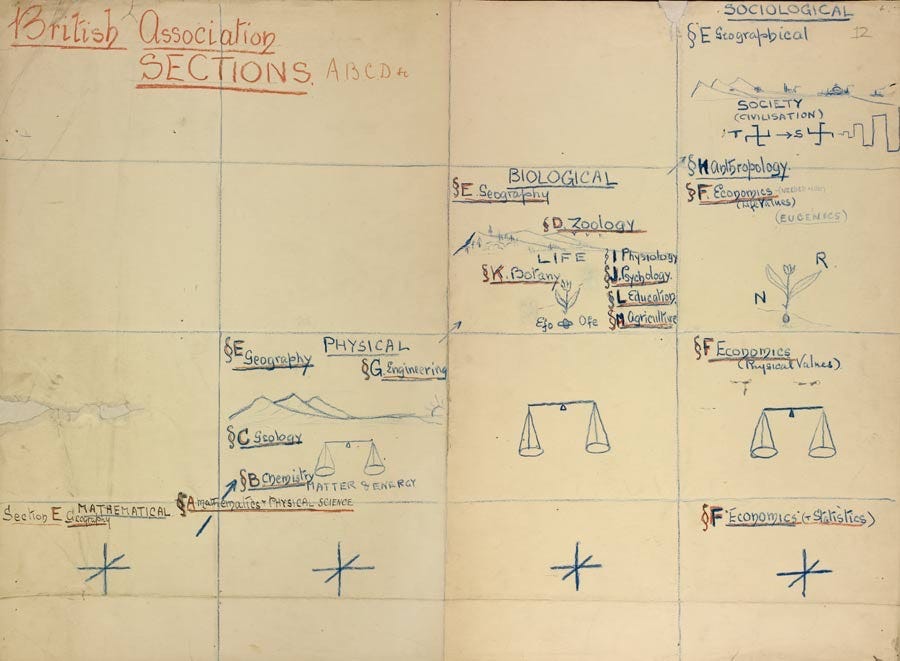

As a somewhat “unschooled” man, with nonetheless a passion for the social power of education, Geddes expressed his ideas in new and engaging ways. He was famous for his “thinking machines,”- these diagrams illustrated his complex ideas and created frameworks for making decisions based on them.

One of his greatest thinking machines survives in Edinburgh to this day. The Outlook Tower, now home to Edinburgh’s Camera Obscura Experience, was built by Geddes as a social laboratory for town planning in Edinburgh. The lower floors of the building provided context from Scotland and Europe, while the camera obscura mechanism on the top floor provided a panorama of the whole city. Visitors therefore travelled through a mass of relevant data before arriving at the top floor to consider how this might apply to the city projected in front of them.

“Geddes said make your decisions based on an evidence base… just like in the natural sciences you observe nature and make your conclusions, well observe humanity in cities to understand your decisions and conclusions,” says Gallacher. He believes that the data-gathering Geddes promoted through Outlook Tower is similar to what is possible with artificial intelligence. With a wealth of information on cities around the world, we can interrogate AI and find good, tailored solutions for our cities, he argues. He plans to develop more on this idea in his talk.

“An opportunity that Edinburgh didn’t seize,”

Geddes’ ideas were popular and influential during his time, not only in Edinburgh but across the world; after Edinburgh, he worked directly in India, France and Sri Lanka, and his ideas about the interactions between people, architecture and environment arguably revolutionised town planning. But sadly in the Old Town, Gallacher argues that Geddes’ legacy has not lived on.

“What would the Old Town look like without Geddes? It is without Geddes; the question is what would it look like with Geddes,” says Gallacher. Geddes’ fundamental goal was to preserve history while making spaces liveable in the modern world. Few would say, in 2024, that the Old Town is an easy place to live in as a normal resident.

Gallacher argues that more public amenities would be first on Geddes’ list of changes were he to rock up in the New Town today. He’d want the Old Town to be somewhere that residents could easily live a modern life; do their shopping, have a social life, get a sofa delivered. Housing and hotels would be planned so that a mixture of people could live in the area.

New architecture and building would be welcome, but it would be coherent with the unique appearance of the Old Town. There would also be more greenspaces; with space becoming scarcer, Gallacher argues that Geddes would be in favour of innovative solutions such as creating greenspaces on roofs and terraces.

Much of Geddes’ ideas, and their applications to the Edinburgh of 2024, seem fairly obvious in 2024. But the self-evidence of his thoughts is only testament to his legacy in our values and aspirations for our urban spaces. Even if not on a conscious level, Geddes’ legacy lives on in Edinburgh. But as debates rage about the impact of Edinburgh’s tourism on the lives of its citizens perhaps it is time to revisit the ideas of the forgotten biologist and sociologist of Riddles Court.