'She never married because all the good men died there'

The greatest rail tragedy in UK history and how it helped shape the unique Leither identity

Private George Nairn lived his life on streets that most of us know.

He was born in Prince Regent Street, which today lies just behind Leith Theatre and Leith Library, although neither of these had been built at the time. The family later moved to Anderson Place, next door to today’s Biscuit Factory music venue. As a volunteer in the Royal Scots brigade, Private Nairn trained at the Drill Hall on Dalmeny Street, which is now the celebrated community arts venue and cafe.

These are the same streets that his great niece, Susan Dickson, grew up on, too. Although Nairn’s parents hailed from Fife originally, the family has since established themselves as, in Dickson’s words, “died in the wool Leithers”.

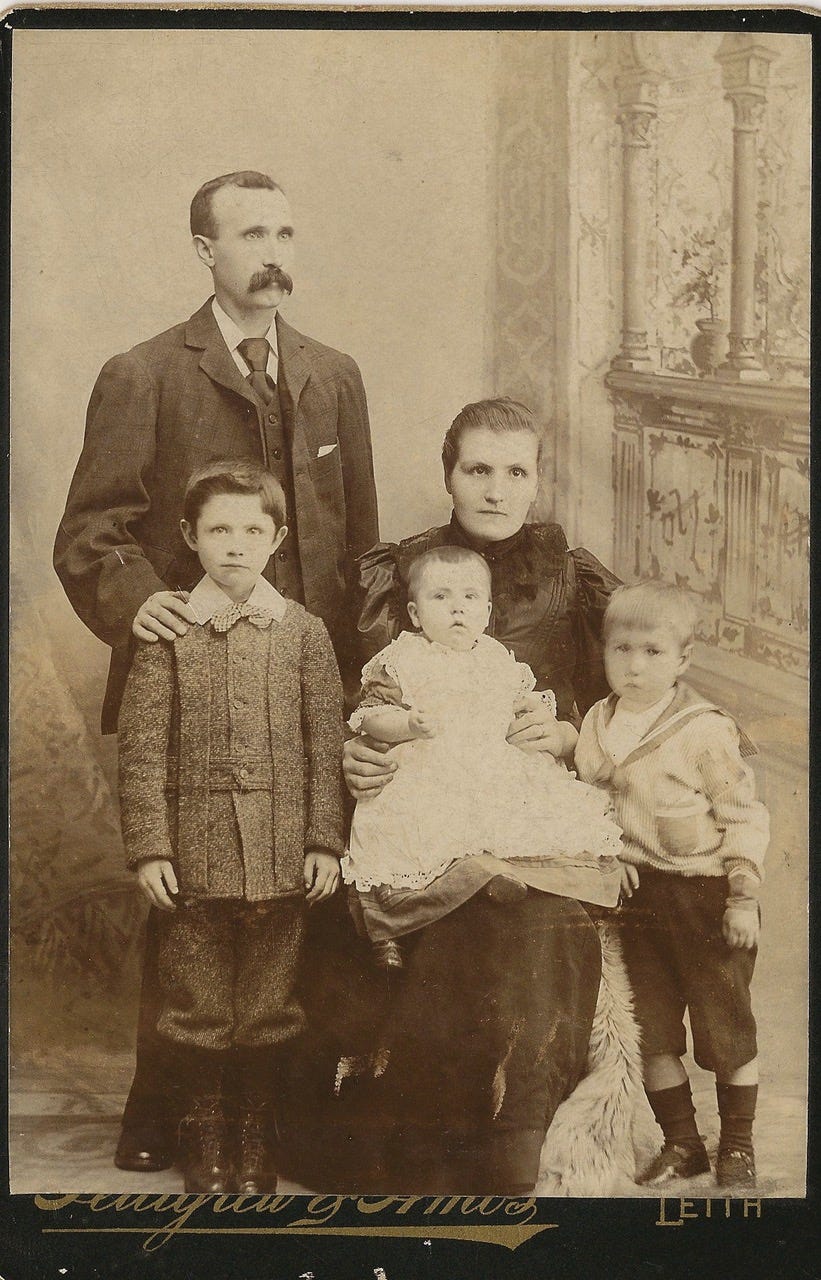

Private Nairn was the second of nine children. His younger sister Agnes would see two more generations of her family grow up in Leith, but Nairn didn’t see any of this. He never saw the construction of Leith Theatre in 1929, or the birth of his nephews and nieces.

Alongside over 200 other young Leithers, Nairn was caught up in the greatest tragedy in UK railway history, which rocked the community for decades to come.

“My gran spoke about the Gretna rail disaster every Remembrance Day. I remember once, we were out in the car at 11 o'clock, she made my granddad pull over in the car, and we had to sit there and observe the two minute silence,” says Dickson.

Gretna Rail Disaster

On 1 May 1915, Nairn and the rest of the 7th Battalion of the Royal Scots Battalion marched out of the Dalmeny Street Drill Hall, headed for Gallipolli. Of the 500 men, at least 215 of them would never make it out of Scotland.

On 22 May, the military train carrying the Royal Scots Battalion collided with a stationary local train at the Quintinshill signal station near Gretna Green. Minutes later, a northbound sleeper train from London to Glasgow collided with the wreckage; all three trains, and two nearby freight trains, were engulfed in flames.

In 2015, a local history project conducted by Out of the Blue, the arts and education trust which now owns and manages the Drill Hall, unearthed details of those affected by the rail disaster. The victims included four members of the Sime family; father and three sons, who resided at 40 Dalmeny Street - their father had been caretaker of the Drill Hall.

Alexander Thomson survived the crash and helped the injured, only to be sent to Gallipolli two weeks later to find the rest of his regiment had been decimated on the battlefield. Two sons of the prominent Salvesen family, who played a major role in connecting the port of Leith with their ancestral Norwegian home, were involved in the crash: while Noel Salvesen was only injured, his brother Christian did not survive.

The lasting impact of a sudden tragedy

The Out of the Blue history project mainly focused on those who were left behind: the Leith community. Families gathered outside the Drill Hall on Dalmeny Street to hear news of their loved ones. Some reports claim a window on the first floor opened, and the names of the dead were shouted down to the crowds. The window then closed. Several of the bodies of unidentified soldiers were also brought back and laid out in the Drill Hall to be identified by their family members.

Fifty of the Royal Scots men were designated “missing”. One of them was George Nairn. Weeks went by without any news for his family; in reality his body had been so consumed by fire that nothing was left. Susan Dickson, Nairn’s great-niece, recalls the stories from her grandmother, who was only nine years old when news of the rail disaster reached the family.

Dickson says that family members went to Quintinshill to search for George, coming back with what was thought to be his rifle butt. “In my Gran's attic for years and years, there was this piece of old wood which was George's rifle butt. Given the circumstances that he was missing, I think something was brought back to make the family feel a bit better,” she says.

Dickson also recalls that her great-aunt Chrissie, who lived in Leith all her life, and, along with many of her close friends, never married. “They all said it was because all the good men died at Gretna,” says Dickson.

Persevere

Memorials to the Gretna rail disaster carry on to this day; the Royal Scots Regiment holds a yearly memorial in Rosebank cemetery where the bodies recovered after the crash are buried. A memorial also stands in Pilrig Park, which would have been a well-known space to many of the victims. This year, Out of the Blue hosted an exhibition from the Royal Scots Museum, which usually sits within Edinburgh Castle, as well as a screening of the documentary film Gretna 100, produced by a filmmaker based in the Drill Hall.

Discussion following the film screening was full of memories and anecdotes, passed down from grandparents to current Leithers. There were stories of meeting train drivers who claim to remember the crash every time they drive the West Coast Main Line, and of locals diligently raking through newspapers and records to unearth the history of this tragedy in their community.

Out of the Blue’s history project included a theatre piece called “Persevere”. The single-word motto of the port town, which has given its name to streets, pubs and poetry in the area for centuries, has also held onto its relevance through to today.

According to Susan Dickson, the event that her grandmother remembered most was not the rail disaster, but the amalgamation of Leith into Edinburgh in 1920, against the wishes of the local population.

Persevere is not just a motto. It is a recognition of a lived experience. The experience of a population that endured tragedy and hardship beyond that seen in most communities. It is perhaps an embodiment of the will power needed to simply keep going in circumstances that would seem insurmountable to anyone who has not lived through.