‘On fire from top to bottom, vomiting out flames like a volcano’

The day the Old Town burned and the rise of the man who changed fire-fighting around the world

It started at 10 o clock. Auld Reekie was settling down to sleep through another dark November night when the cry rang out, echoing from one closely packed home to another. “Fire! Fire!”

Soon the wynds and closes were filled with people, fleeing their homes and coming out to investigate.

It was November 15, 1824, and the cry struck terror into the inhabitants of Edinburgh densely populated Old Town. On this occasion, the fear the warning call brought was justified. The Great Fire of Edinburgh, which would rage for days, left 13 dead, destroyed around 400 homes, and left almost 500 families homeless.

It happened just as Edinburgh’s Enlightenment had neared its end, when the city’s culture and learning was admired around Europe, and was witnessed by the city’s great and good. Sir Walter Scott saw it unfold and wrote: “I can see no sight more grand or terrible than to see these lofty buildings on fire from top to bottom vomiting out flames like a volcano from every aperture.”

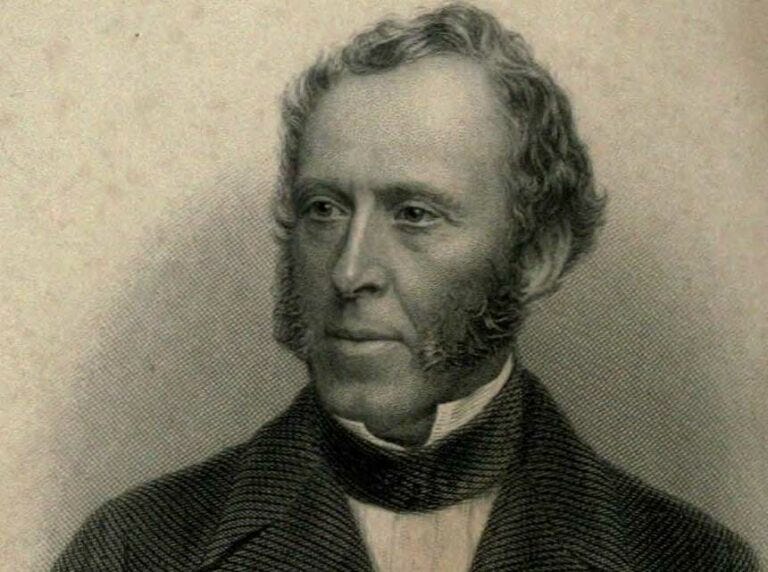

Some positives would be wrought from the ashes of disaster. Swathes of sub-standard, overcrowd and unhygienic housing were subsequently destroyed in the Old Town. It also started a revolution in the way fires were fought in Scotland’s Capital and ultimately much further afield. One James Braidwood, aged just 24, had a few weeks earlier taken up post as the first Master of Fire Engines, tasked with delivering a municipal fire service. He is still revered around the world as the father of modern fire-fighting.

Sermons and Steeples

The fire started in the home of well-known engraver James Kirkwood, a respected craftsman, thought to have been caused as he heated a pot of linseed oil used in the trade. The Kirkwood family has continued through multiple generations and still produces highly-skilled engraving in the city today.

It seemed to have been brought under control and extinguished throughout the night, after ripping through six multi-storey tenement homes. By the following morning, smoke was seen coming from the Tron Kirk, and soon its wooden steeple was ablaze. Again, the fire took hold.

In his autobiography “Memorials of His Time” the eminent lawyer, judge and writer Henry Cockburn – of Cockburn Street and Cockburn Association fame - wrote: “We ran out from the Court, gowned and wigged, and saw that it was the steeple, an old Dutch thing, composed of wood, iron, and lead, and edged all the way up with bits of ornament.

“Some of the sparks of the preceding night had nestled in it and had at last blown its dry bones into flame. There could not be a more beautiful firework; only it was wasted on the day-light. It was one hour’s brilliant blaze. The spire was too high and too combustible to admit of any attempt to save it, so that we had nothing to do but to admire.”

Sir Walter Scott too was on the scene, as Cockburn recounts: “When it was all over, and we were beginning to move back to our clients, Scott, whose father’s pew had been in the Tron Church, lingered a moment, and said, with a profound heave, ‘Eh Sirs! mony a weary, weary sermon hae I heard beneath that steeple!’ “”

Again, throughout the day, the blaze appeared to be burning itself out, but there was more to come. By around 9.30pm, Cockburn noticed the sky was “unnaturally red.” He said: “I hurried back and found the south-east angle of the Parliament Close burning violently. This was in the centre of the same thick-set population and buildings; but the property was far more valuable. It was almost touching Sir William Forbes’ bank, the Libraries of the Advocates and of the Writers to the Signet, the Cathedral, and the Courts.”

Confusion reigns as fire blazes

After a serious fire earlier that summer, the decision had been taken to appoint James Braidwood. However, that had only been in place for a few weeks, and there had been little opportunity to train the recruits or equip them.

Rather, confusion reigned, as Cockburn described: “Of course the alarm was very great; but this seemed only to increase the confusion. No fire ever got fairer play. Judges, magistrates, officers of state, dragoons, librarians, people described as heads of bodies were all mixed with the mob, all giving peremptory and inconsistent directions, and all, with angry and provoking folly, claiming paramount authority.

“It was said to have been mooted, and rather sternly discussed, on the street - whether the Lord Provost could order the Justice-Clerk to prison, or the Justice the Provost, and whether George Cranstoun, the Dean of the Faculty, was bound to work at an engine, when commanded by John Hope the Solicitor-General to do so, or vice versa.

“Then the firemen were few and awkward, and the engines out of order; so that while torrents of water were running down the street, nobody could use it. Amidst this confusion, inefficiency, and squabble for dignity, the fire held on till next morning; by which time the whole private buildings in the Parliament Close, including the whole east side, and about half of the south side, were consumed.”

The next day, the scale of the devastation was evident. Scott described it thus. “Between the corner of Parliament Square and the South Bridge, all is destroyed excepting some new buildings at the lower extremity and the devastation has extended down to the closes which I hope will never be rebuilt on their present or should I say late form. The general distress is of course dreadful.”

Two firefighters were among the dead.

The City rallies

Ruins had to be brought down and made safe, with Royal Navy sailors, miners and sappers using explosives to collapse the most dangerous. A report in The Scotsman on November 17 described the scene as ‘wild, terrific, and sublime’ but added “a nearer approach changed the feeling. Pity was excited by the condition of the poor – men, women, and children, driven from their houses, carrying in their hands some miserable remnant of their furniture but without a penny to obtain food, or a house to shelter them”.

A fund was set up to help, and within a year the total sum collected amounted to £11,702 (worth more than £1.6 million today) of which only £6,699 had been disbursed to the needy. Most of the balance was converted into a fund for the relief of firemen who might be hurt in the execution of their duty or to support their families in the event of their death.

Much has been written of the 200th anniversary of the appointment of Braidwood, who went to work with a vengeance after The Great Fire. New engines and equipment were ordered, the city was split into four districts each with its own station, and men were recruited for their knowledge of buildings and trained up to fight fires.

Braidwood the pioneer

Braidwood brought professionalism to fire-fighting, drafting everything from regulation uniforms to techniques still used around the world today. Firemen entering buildings to fight fires at their source – dangerous but effective; the use of ladders to fight fires and aid escapes; even designing new breathing apparatus.

Within a relatively short period of time, Edinburgh’s municipal fire service, the first in the world, was an exemplar of good practice, with Braidwood’s advice being sought far and wide. Fame of his personal courage was growing – on one occasion rescuing nine people and on another single-handedly carrying barrels of gunpowder from a burning building.

Inevitably he was “poached,” with an approach to repeat his Edinburgh work on a grander scale in London. He achieved this, and more, and again became a legendary figure for the service he established in the metropolis with its 1.5 million people.

It was there he was to die, in a huge fire, on June 22, 1861, in an enormous dockside warehouse in Tooley Street – a building whose construction he had tried to limit forecasting that “no power on earth” could extinguish a fire that took hold in it. He was buried in a collapse of burning rubble after ensuring his men had retreated to safety.

Paul Hashagen, a retired New York fire chief and author, takes up the tale: “Dozens of firemen scrambled to the pile of flaming debris, trying to dig toward their chief. Another explosion above them drove them back, away from the blazing structure. They stood helplessly as the fire, now burning 500 feet along the waterfront and hundreds of feet deep toward the city, defied their efforts to reach their leader…

“On Monday morning, it was decided to make another attempt to recover Braidwood’s body. Under extreme danger, firemen began the difficult search. At 5 p.m., Alfred Dozer, Braidwood’s trusted aide, found his chief’s body. Then, with dignity and reverence, Superintendent James Braidwood was carried from the fire…

“On Saturday, June 29, 1861, a huge funeral was held for the fallen leader. The turnout rivalled a royal send-off. The fire burned for two weeks.”

The Edinburgh pioneer revered by Hashagen as the “father” of modern fire-fighting had gone. But his impact continues to be felt wherever firefighters are called to duty.

To learn more about the fire service, and James Braidwood, a visit to the Museum of Scottish Fire Heritage in Dryden Terrace is well worth a visit Museum of Scottish Fire Heritage