It will kill 40,000 sea birds to help hit our Net Zero targets

Will the green energy from the giant Berwick Bank wind farm come at too high a price for the Forth’s wildlife?

Every year, millions of seabirds make the Firth of Forth their home. Its many sheltered bays, rocky cliffs and remote islands make it ideal for nesting, breeding and raising young.

Bass Rock, known for its white poo-stained appearance, is home to the world’s largest colony of Northern Gannets. The island is so synonymous with gannets that it gave the bird its scientific name — Morus bassanus.

The similarly avian-friendly islands of Fidra, Craigleith, and The Lamb, as well as the cliffs at St Abb’s Head, support significant seabird populations including puffins, kittiwakes, cormorants, shags, terns, guillemots and razorbills. At least 250 different bird species have been recorded on the Isle of May alone, which hosts 100,000 breeding puffins.

“It’s an absolute Mecca of life for seabirds,” says Emily Burton, conservation manager at the Scottish Seabird Centre, based in North Berwick. “We’re incredibly lucky to have this wealth of wildlife here on our coasts.”

Populations are shrinking

It’s not just feathered friends. In addition to the resident grey seals, sightings of whales, dolphins and even sharks in the Firth of Forth have been on the rise in recent years. Meanwhile, oysters are returning to the estuary after 100 years thanks to a huge restoration effort.

But this relative abundance hides the fact that over the last few decades seabird populations have been steadily shrinking. The number of breeding seabirds in Scotland has declined by almost 50% since the 1980s, according to NatureScot.

Among the top drivers is climate change. As sea temperatures have risen, the fish seabirds rely on for food are moving deeper or further north to cooler waters, explains Burton, pushing feeding grounds further away from the coast.

In recent months, a more immediate threat has emerged from an unlikely source.

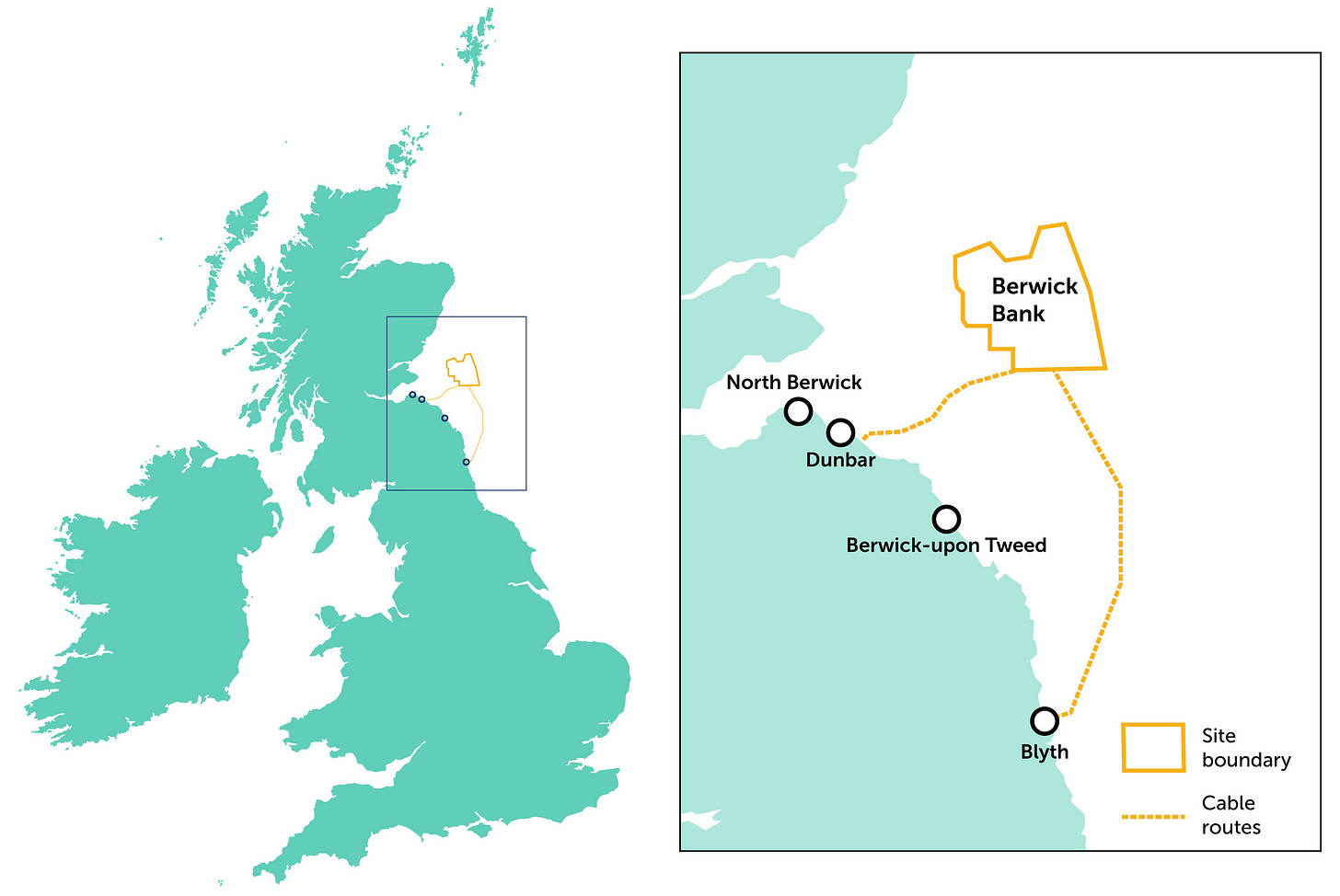

In July the Scottish Government approved plans for a vast offshore wind farm at Berwick Bank, 30 miles from the East Lothian coast and squarely in the stamping ground of these internationally significant seabird populations.

Predicted to result in the deaths of tens of thousands of seabirds — far more than other UK wind farms — it is staunchly opposed by a coalition of conservation charities, including the National Trust and the RSPB.

At 307 turbines, Berwick Bank is set to be one of the world’s biggest offshore wind farms, stretching across an area of ocean four times the size of Edinburgh.

Leap forward in carbon reduction

Crucially, it would represent a leap forward for Scotland and the UK’s efforts to tackle climate change. With a whopping generation capacity of 4.1 gigawatts (GW), Berwick Bank would single-handedly close the gap with Scotland’s current target to reach at least 8 GW of offshore wind capacity by 2030, up from around 4.2 GW today.

SSE Renewables, the developer, is a giant in the offshore wind industry. It has contributed to the construction and operation of three existing wind farms in the North Sea: Seagreen near Arbroath, Beatrice near Caithness, and Greater Gabbard off the Suffolk coast.

The company also has the largest pipeline of offshore wind projects in the UK and Ireland, at 9 gigawatts (GW), which includes Dogger Bank, currently under construction off the Yorkshire coast.

This new wind farm could displace eight million tonnes of carbon dioxide a year, according to SSE — similar to removing all of Scotland’s car emissions. The firm’s ecology manager said: “To put it simply, the Scottish Government’s targets of net zero will not be met without Berwick Bank.”

Mortalities in fragile environment

But, in a fragile marine environment, a project of this scale has side effects.

The Scottish Government’s own assessment shows that Berwick Bank is predicted to kill 2,808 guillemots, 815 kittiwakes, 261 gannets, 154 razorbills and 66 puffins every year. The National Trust points out this will amount to losing more than 40,000 birds in the estuary over two decades.