"If you can't solve a problem, build a bigger telescope..."

The Edinburgh science star battling Long Covid to help us understand the universe - and ourselves - a little better

Blackford Hill offers winding forest trails, stunning panoramic views of Edinburgh, Fife and the Pentlands, and, if the clouds clear after sunset, a view of our glittering night sky, writes Sarah McArthur.

The stars have sparked curiosity and wonder down through the millenia, and from ancient times people have gazed upwards, wondered and studied. The science of Astronomy has been with us from the first civilisations - from the ancient Egyptians to the Mayans. The ancient Greek philosopher Plato told us “Astronomy compels the soul to look upwards, and leads us from this world to another.”

One of Edinburgh’s familiar landmarks, The Royal Observatory was established near the 164m summit of Blackford Hill in 1822, and its visitor centre still attracts children and grown-ups alike to marvel at the wonders of the universe.

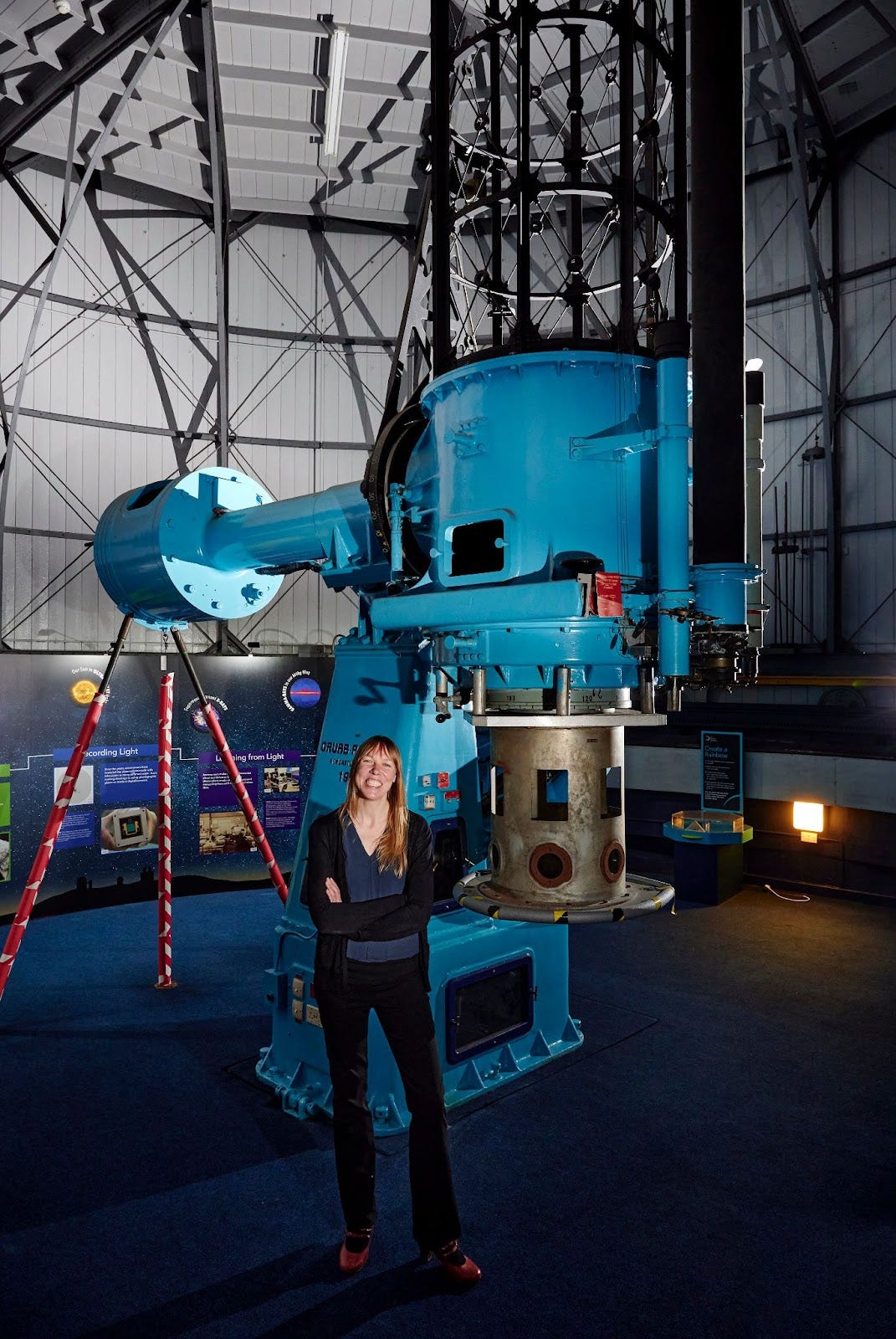

What those visitors may not know is that the Observatory is also home to an eminent scientific community at the cutting edge of astronomy, and one of their leaders is Professor Catherine Heymans, Astronomer Royal for Scotland.

“It always fills me with joy that I'll be working in perfect silence and then thunder thunder thunder thunder as the children run in because they're so excited to see the gallery and all the different things up there,” says Heymans, as she explains to me why she's based her very international scientific career in Scotland’s Capital city. “In Edinburgh, it's really unique in terms of astronomy... You don't find that anywhere else in the UK that has a combination of university, government laboratory, science education, and science in industry all in one place.”

The Astronomer Royal for Scotland is a post similar to that of a chief scientific advisor or the head of a scientific society; awarded to a leader in the field of astronomy in Scotland. Heymans certainly lives up to the title; her previous work includes world-leading techniques to map the dark matter in the universe, and she is currently a professor at Edinburgh University as well as the head of the German Centre for Cosmological Lensing at the Ruhr University.

Heymans also describes her role as “the port of call for any questions about astronomy” and appears regularly on television, radio and in government advisory panels. She has a rare talent for both doing and explaining complex astrophysics. She describes dark matter and dark energy, the subject of her research:

“If I look at the physics I learned at university, it can explain our reality here on earth, what we're made up of, how the planets orbit the sun, we really understand the gravity of our solar system incredibly well we understand the particles that make up our body, how light works, things on earth we understand really well. But when we look out into the universe, there's a disconnect between the physics that explains everything here on earth and how things work out in space. And to connect the divide there we need to include two other ingredients that we don't know or understand here on Earth- and we call them dark matter and dark energy. And they're essential ingredients to explain what we see in the universe but we don't really understand what they are.”

So how is Heymans unravelling these mysterious cosmic ingredients?

“If you can't solve a problem, build a bigger telescope- that's usually our strategy” she says. Heymans is again a leading figure in a global collaboration to build a huge telescope with the world's largest camera at the Vera C. Rubin Observatory (VRO) in Chile. The project sounds like it comes out of a sci-fi film; an enormous telescope on the top of a mountain in the middle of the Chilean desert, surveying the night sky for killer asteroids. Yes, you heard that right- the US-government funded project will be able to track the path of almost every object moving through space which might potentially obliterate planet Earth. But the data recorded over ten years will be useful for thousands of scientists around the world, too.

Heymans is keenly awaiting the details of the distant universe in the background of the VRO images, which will help to answer the big questions of how our universe works, what it's made up of, and even how it will all end.

Making science accessible

Heymans speaks with evident wonder and excitement about her groundbreaking research - and she talks equally passionately about the other half of her work, in opening access to astronomy and the sciences in general. “Science not talked about is science not done as far as I'm concerned,” she says.

“Children love astronomy - everyone loves astronomy- people come to it from lots of different angles – some people from the sheer beauty and awesomeness of it… and other people come at it from the science side of what's going on in the stars I can see, are there planets is there life on those planets. I don't know anyone who doesn't love some sort of astronomy and so it's a great way to get people into science,” she says.

But as the first female Astronomer Royal, who was taught by an all-male staff at the University of Edinburgh in the late 90s, Heymans is acutely aware that not everyone has an even shot at turning that star-struck wonder into a career.

“There's lots of different research on why science is still very much dominated by privileged white males and there are lots of little things you can do but I think the root cause of this is culture... different jobs are still associated with different types of people... every time I get asked to go on the radio or television I say yes because I need people to see that an Astronomer Royal isn't a privileged white male,” she says.

Heymans says that there has been good progress since she was an undergraduate; the percentage of women in science is now about 25 to 30%. Crucially, this proportion is now constant from high school right up to PhD level, when before the percentage of women would have decreased in the higher levels of study. But the issue still remains of getting girls into science as teenagers, as well as opening access to other demographics. “Most of the research is done on women but if you ask the question of people from disadvantaged backgrounds or people of different ethnicities it's significantly worse,” Heymans explains.

Heymans was inspired herself as a young teen by a combination of a fantastic (female) physics teacher, an opportunity to see Haley's comet through a telescope, and a family holiday to a dark sky area in Scotland.

Since she was nineteen Heymans has been devising a way to give the same experiences to young people from all backgrounds. As a student working in a bar on Causewayside, she organised an unofficial free tour of the Royal Observatory for the regulars' kids. She particularly remembers one lad whose complete demeanour changed when she convinced him that the close-up image of Saturn through the Observatory telescope was real, and not just a sticker or a photo.

“He just changed just like that, from this really cool hard I don't care, this is rubbish, why am I even here, to just this child-like, excited, awed wonder that he'd actually seen the rings of saturn with his own eyes. And that was when I decided I wanted to make that happen for not just the affluent kids who had parents who would bring their kids to a place like the royal observatory, but to everyone.”

This September, her aims will finally be realised, when Edinburgh school pupils go on residential weeks to Outdoor Centres in the Highlands. The two Edinburgh Council centres at Benmore and Lagganlia are now equipped with telescopes and staff training to run star-gazing evening sessions allowing kids to see galaxies, stars; maybe even the rings of saturn. The smart-telescopes use new technology which gives users a list of the objects currently visible, and automatically point towards the object the user wants to see- all controlled from a smartphone. This not only lets young people choose what they see, but also removes the burden from outdoor centre staff to operate complex manual telescopes.

If the trial with Edinburgh schools is a success, Heymans hopes to raise money through the Royal Observatory Trust to roll the project out to residential centres for all Scottish schools.

Long Covid

The sheer volume of work Heymans produces is extraordinary; particularly her work in the last two years, which she has done while managing long covid. While long covid has turned Heymans' life upside down, she is determined not to let it define her.

“We laugh in the face of adversity,” she says with only a hint of irony. “You have to be aware of what your limitations are, and once you've got over being really cross, upset and frustrated about those limitations you have to modify your life to work within those limitations.”

Heymans now works in thirty-minute bursts, interspersed with naps. She says that after a predictable thirty minute period she can feel the fatigue coming, “it's like your battery gets pulled out of your back and you just collapse.” She compensates for her short working days with a seven-day work week, and keeps herself going with hyperbaric oxygen therapy, provided by Leith-based charity Compass. The charity has been offering the treatment to patients of neurological conditions for forty years.

While she misses her office in the scientific community of the Royal Observatory, she is grateful that she has a career and a life which is flexible to her condition. “I am incredibly privileged. I don't have the stress of a job that's requiring me to be in and on my feet all day, and I have amazing support networks from my family and that level of privilege allows me to be happy and positive- and that's not true for lots of people with long covid.”

Compass has also provided Heymans a community of people with invisible and ignored illnesses. “People say we've never seen anything like long covid but we have, it's called myalgic encephalitis or chronic fatigue syndrome (MECFS). ” While Heymans believes long covid is ignored because the government and the public simply can't face more awful impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic, the lack of visibility for MECFS is a result of gender bias. “It is a condition that has been ignored for decades because it particularly affects women, it's been told that these women are psychosomatic, it's all in their heads, they're making it up... had those women been taking seriously had any decent funding been given we wouldn't be in this situation with long covid.”

Just like her career in a male-dominated science, Heymans' experience of chronic illness has made her aware of biases in our society and healthcare- including her own biases.

“I used to have a very ableist mindset,” she says, reflecting on life with a disability, as someone who used to run and cycle all over the place, and was on the go every minute of the day. “My previous ableist mind would have thought living like this would be absolutely terrible, and it's not. There's joy and love and happiness to be had, it's just different.”