‘I shall be buried there, when I have given what the others gave’

The extraordinary story of the life and death of Edinburgh’s forgotten war poet

He lies at Aubignon. His memorial is one pale stone amongst the thousands that stretch like a vast regiment, lined across the green fields of northern France. Like soldiers standing to attention.

It is a sad, simple and fitting memorial to a young man who was both soldier and poet, an instinctively light-hearted optimist but also a deadly serious leader of men whose comradeship he loved. Killed, less than a week after turning 21, by shrapnel, in the fierce heat of mechanised warfare and the bitter cold of winter.

He died from injuries suffered on the first day of one of the most bloody and important battles of the Great War. He died where 18,000 Scots died, thousands more than at Flodden, Culloden, and the bloody fields of Waterloo in nearby Belgium, combined. At Arras.

Second Lt AJ “Hamish” Mann is perhaps a small part of Edinburgh’s rich history, and just one human part of the history of the First World War, but he is an important part of both.

His is no ordinary story. Alexander James Mann, known to all as Hamish, had been a schoolboy at George Watson’s College who dreamt of a career writing and acting, and showed great promise in both. But this would-be actor-poet’s determination to serve his country in war, despite suffering from a heart condition that had seen his first application to serve rejected, would see the curtain fall on his young life and growing talent in the most brutal of theatres – that of war.

Yet we would know nothing of this tale were it not for the discovery of 3000 pages of his writings, notes, ideas, in a chest in a city attic. They were found by his great niece and nephew as they cleared their parents’ home, which had been sold to help pay for residential care for their mother.

This week that unique archive, which had been valued at £3000-£4000, had been due to be auctioned at Lyon & Turnbull in Edinburgh. At the end of the day, and understandably, his family could not bear to let it go. But their discovery has ensured the spotlight has fallen once again on a life filled with promise, with courage, with laughter, with friendship.

Rosemary Stewart, who sorted through the find with brother Robert, told the Inquirer: “At first it appeared to be yet more linen – we had come across a lot of linens. But when we lifted the top layer, we found all of these documents and writings and took them back home.”

The task of reading through them all proved arduous. Rosemary said: “I would sit and read through them with tears pouring down my face. It was just so heart-rending.”

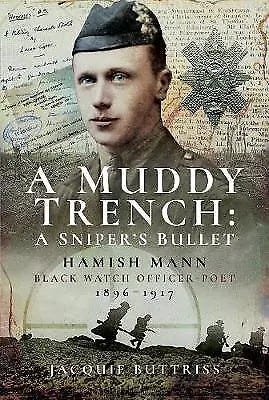

A family friend, Jacquie Buttriss, offered to further sort through the documents and then write a book about Hamish and his life. “A Muddy Trench: A Sniper’s Bullet” was the fascinating and moving result, published just before the centenary of the ending of the war. But while this revived interest in Hamish’s life, it was not for the first time.

Following his death, his mother Charlotte sorted through his papers. She found a hardbacked notebook with his plan on what he wanted contained in his first book of poetry, which he hoped to have published. She faithfully sorted through his papers, sorting the poems he had picked into the required order, and she and husband Alexander had the book published for family and friends, although it received wider attention. A handful of copies of “A Subaltern’s Musings” are known to remain.

At the outbreak of war, Hamish volunteered like many young men of his day but was not considered fit to fight as an 18-year-old with heart problems. However, his doctor, also a Territorial Major in the Army Medical Corps, offered him a voluntary position at Craigleith Military Hospital (now the site of the Western General Hospital). Here, Hamish put his gift for words to good use, helping to establish the magazine, the Craigleith Hospital Chronicle.

Casualties Mount

As casualties mounted, the War Office changed requirements needed to sign up. Hamish volunteered again, and this time passed the medical examination on 2nd June 1915. Long months were then spent on basic training and subsequent officer training, before in 1916 an impatient Hamish was shipped to take charge of his platoon in D Company, 8th Battalion, The Black Watch in northern France.

He was to survive his first major engagement, at the Somme, over the summer and autumn of 1916, with Britain losing 57,000 men on the first day alone, the nation’s greatest military losses in a day.

Throughout the following weeks they advanced six miles, significant but without capturing targeted gains. Despite all he had now witnessed Hamish retained his desire to act bravely and to do his duty, as exhibited in these lines from “Before”, written when he was still 20 years old during The Battle of the Somme in October:

Let memory and tenderness be mine.

And may I die more nobly than I live

(For I have lived in folly and regret):

Then in the last Great Moment when I pass,

I shall have paid my Life’s outstanding Debt!

Then came a bitterly cold winter, and a frozen stalemate followed as the two sides dug in again. Falling temperatures became the enemy, with sub-zero weather risking frostbitten legs for the Highland regiments, yet the majority flatly refused to wear trews as opposed to the kilts for which they were famed. Instead, legs were wrapped in field bandages.

He was worshipped and loved

As winter gave way to spring in 1917, with the weather improving albeit still very cold, the Allies were determined to make another big effort to advance, this time in the area around Arras. Hamish and his men were amongst the first wave to go over the top on 9th April at zero hour, 5am, following a massive artillery “creeping barrage” designed to clear a path through the jungle of wire in no man’s land.

Within a short time, Hamish suffered a serious wound to his leg when a shell exploded close to him. One of his men, Lance Corporal James Watters saw him fall and went to his aid, noting a badly bleeding leg wound to which he applied a field bandage. Watters defied an order to leave the fallen officer and continue his advance until Hamish’s batman, James Morris, joined them. Only then would Watters move on and was himself severely wounded soon after. He later wrote to Hamish’s parents, describing him as “the finest officer of the Battalion.”

“He was worshipped and loved by all the men of the ‘Fighting 14.’ He was with the men in everything they did, and in return we knew he loved us. He was only a mere boy in years, but thank God he was a soldier and a gentleman, and one whose name will always be remembered by the men of 14 Platoon.”

As coincidence would have it, Watters was treated at Edenhall Hospital in Kelso for his wounds, and while there met Sister Jean Henderson, Hamish’s older sister. It was Watters who told her how her brother had perished.

Hamish’s immediate superior and friend, Captain Robert Murray, also wrote a heartfelt letter to the grieving parents: “There were two complete sides to his character. There was the Mann of the parade ground, smart and soldierly, prompt in the discharge of his duty, a true product of the New Armies. And then there was Mann the Shawian, the Fabian, the actor, the poet with his quaint sayings and his mock cynicism, and his heart of gold. This was the Mann we knew and loved best.”

So cold they thought he was dead

There is sadness in the story not only because Hamish’s young life ended, but also at the way it ended. He lay, bleeding, his now also injured batman with him, as falling sleet turned to snow. Medical orderlies found him half-lying in the shell-hole, covered with a light dusting of snow. He was so cold they thought he was dead, checked his identity disc and stuck his rifle upright into the ground with his helmet on top to mark his body. Then they reported him killed in action.

Several hours later they did another sweep, and this time one of the orderlies noticed that Hamish was still breathing and an ambulance was summoned. In the ambulance, no pulse could be found and he was again pronounced “killed in action.” There was then one final change of mind. Buttriss speculates in her book that perhaps as his frozen body warmed in the vehicle signs of life returned, and he was taken to No 42 Casualty Clearing Station at Aubigny, six miles from the front. Here he was admitted as “wounded.” He is finally recorded as dying from his wounds the following day, 10 April, time unknown.

While his own words give us great insight to his life, his headstone gives us only the briefest of details, but perhaps he wrote his own epitaph just weeks earlier, when in anticipating “the big push” he wrote “A Subaltern’s Soliloquy.”

Once did I ask that I be laid to rest

On some wild hillside where the

Grasses sway;

But now, meseems, my resting place will be

Where rifles fire and red blood runs

All day.

I cannot ask for winds to mourn my

Dirge

Or wailing whaups to wheel above

My grave;

I shall be buried with the others

There,

When I have given what the others gave