How Lothians' former coalmines could heat our homes again

Award-winning engineer Corey Boyle on the sustainable heating resource that lies below thousands of our homes

Deep beneath the former mining towns that surround Edinburgh lies a buried resource capable of heating homes and supporting local jobs once again. It comes from the same underground workings that once powered industry, shaped communities, and defined local economies for generations.

But this is not coal.

When the mines closed and the water pumps turned off, groundwater flooded the tunnels and workings below ground, absorbing heat from the surrounding rock. That stored heat, continually replenished by the Earth’s natural geothermal properties, can now be recovered to provide renewable, sustainable, and low-carbon heating. This resource is known as minewater geothermal (MWG), and you may begin to hear a lot more about it considering 25% of every building in the UK is above a mine. That is the equivalent of a staggering 9 million buildings.

Scotland’s Mining History

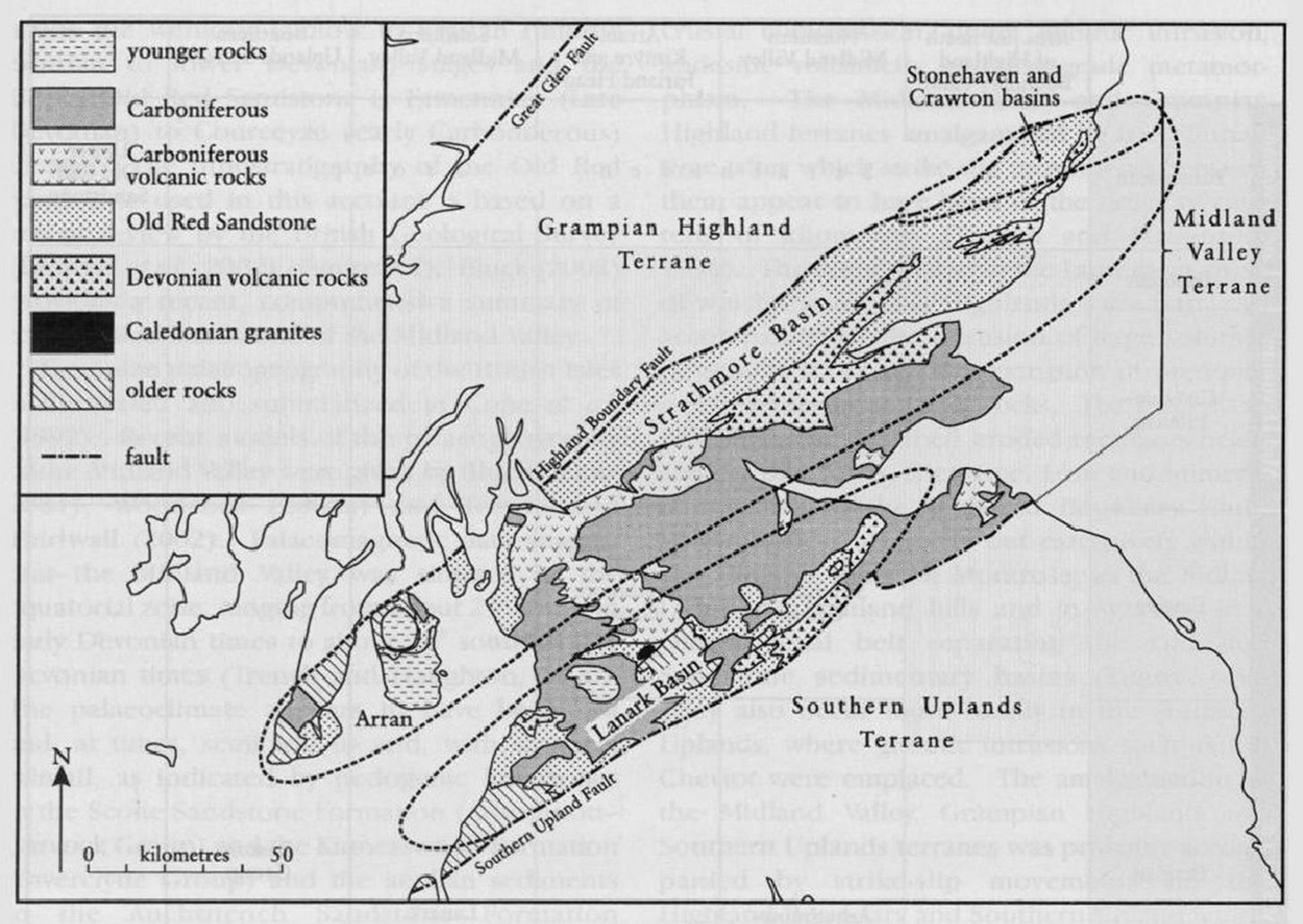

Mining in Scotland stretches back more than 800 years, with coal being extracted as early as the 12th and 13th centuries. During the Industrial Revolution, demand for “black gold” surged and mines spread rapidly across Scotland’s Midland Valley. The map below shows the main Carboniferous coalfields, named after the Carboniferous geological period, when the coal itself was formed, running east to west across the Central Belt and covering large parts of the Lothians and Fife.

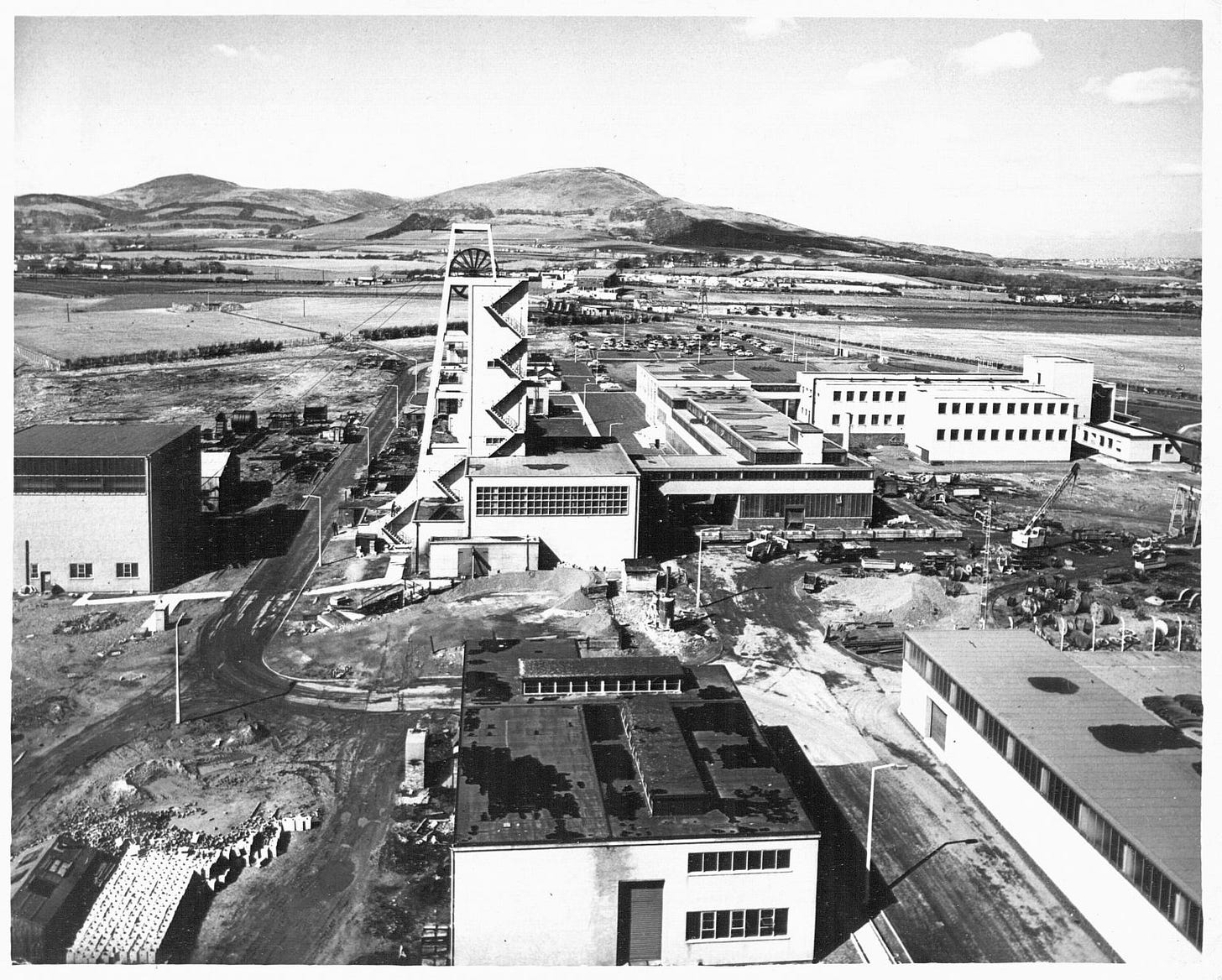

At its peak after the Second World War and nationalisation in 1947, Scotland had hundreds of mines, over 400, extracting primarily coal, along with shale, iron, and other minerals. At the industry’s peak, there were around 60 in the Lothians alone. These mines not only supplied energy for homes and factories but also shaped the towns themselves, creating tightly knit communities and economies centred on the pit.

When the mines began to close in the second half of the 20th century, the impact was profound. Towns that had relied on mining faced unemployment, depopulation, and derelict landscapes, while families lost both income and the social structure built around the industry. Entire communities had to adapt to a post-mining economy, leaving a legacy that is still visible in the towns and hillsides of the Lothians and Fife today. But those abandoned mines now hold a surprising renewable energy resource.