Child slave, soldier, inventor, publican - the extraordinary life of 'Indian Peter'

The pioneering marketeer who changed the face of Edinburgh

The Truth, Oscar Wilde told us, is rarely pure and never simple but it can be stranger than fiction…especially if we accept that it can be a little elastic. But factually-stretched or not, the real-life story of one of Edinburgh’s most colourful historic characters is the stuff of Hollywood blockbuster.

You will find no monument to him. No portrait hanging on the walls at the National Galleries. But, if you know where to look, he has been immortalised - in Scottish poetry, and in our legal history.

Let’s dive then, into the extraordinary life of Indian Peter.

“Who?” I hear you ask. Take a deep breath, this essential summary will take a while and we may not be up for air for some time…

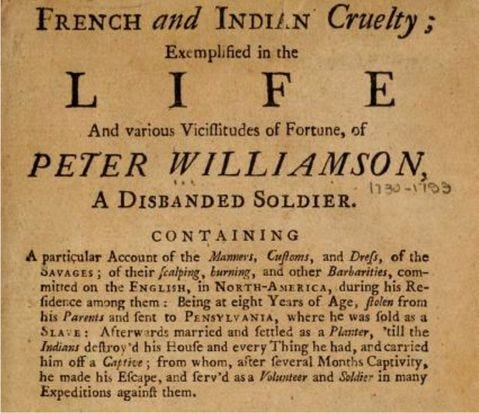

Then just plain Peter Williamson, he was abducted from Aberdeen as a boy, survived trans-Atlantic terrors to be sold and enslaved in the New World; then he was freed by a kindly “owner,” was married and became a pioneer landowner, before he was captured by Red Indians and then escaped. He was a soldier and officer in the French and Indian War, was wounded, captured again by the French before being returned to Britain in a marathon sea journey. Heading home to Aberdeen, he walked from England’s south coast to York, then published his autobiography to fund the rest of his journey home while posing in Indian costume (earning his flamboyant soubriquet); and on his final return home was promptly sued for libel and banished as a vagrant by the corrupt merchants of his native city.

And now breathe…phew. But just for a second, if you please, because it doesn’t end there. Oh no. He then travelled to Edinburgh where he became a friend to the legal profession who encouraged him to sue (successfully) his abductors. Twice. He also became a coffee shop owner and publican; an inventor and innovator; was the first man to produce an Edinburgh Directory in 1773; invented lots of printing-type stuff; and pioneered the penny post system gaining an annual pension in return.

Sorry, nearly forgot, he was twice mentioned in the poems of Rabbie Burns’ hero, Edinburgh’s own Robert Fergusson.

Not a dull life, eh? This was not a guy who lacked energy or excitement in his life. In fact, his adventures make Cap’n Jack Sparrow in Pirates of the Caribbean seem a bit of a snooze-fest. Budding screen writers take note - there must be a movie in there.

SPIRITED AWAY

Peter Williamson was born in the early 1730s, in a croft in Aberdeenshire, and at a tender age was sent to live with a maiden aunt in the Granite City. We know that in 1743, he was kidnapped while playing on the quayside in Aberdeen. At that time there was a lucrative trade in kidnapping children and stealing them off to slavery, often to North America. The kidnappers were known as “spirits.” Several Aberdeen Bailies were suspected of colluding with these traffickers, and when the trade was at its height for two decades it is estimated that around 600 youngsters were taken.

Peter later wrote of his plight in his less-than-snappily titled autobiography “French and Indian Cruelty, exemplified in the Life and various Vicissitudes of Fortune of Peter Williamson, who was carried off from Aberdeen in his Infancy and sold as a slave in Pennsylvania.”

In his memoirs, he described the abduction thus: “Playing on the quay with others of my companions, being of stout, robust composition, I was taken notice of by two fellows belonging to a vessel in the harbour, employed (as the trade then was) by some of the worthy merchants in the town, in that villainous and execrable practice called Kidnapping.”

He was sold into slavery for £16 following a hellish journey across the Atlantic. He then enjoyed his first piece of good fortune, being bought by a fellow Scot, Hugh Wilson, who had been an indentured slave years earlier and had sympathy for young Peter’s plight. Williamson described Wilson as a “humane worthy, honest man. Having no children of his own, and commiserating with my unhappy condition, he took great care of me.” In fact, in his will Wilson left his young compatriot money and a horse with which to seek his fortune.

By the time he was 24 he had met and married the daughter of a plantation owner near the Pennsylvania frontier and was given a house and 200 acres of land of his own. His wife was visiting relations when, on the night of October 2 “how great was my surprise, terror and affright when about 11 oclock at night I heard the dismal war-cry, or war whoops, of the savages which they make on such occasions and may be expected, Wouch, woach, ha, ha, woach, and to my inexpressible grief soon found my house was attacked by them.”

LIFE AS A PACK MULE

His home was burned, he was captured, and spent several months being, in his own words, a “pack-mule” for his Cherokee captors, being forced to watch multiple killings, scalpings and atrocities (described in gory detail, be warned) before escaping to make his way to his father-in-law’s home, to learn that his wife had died in his absence. He was called before the Philadelphia State Assembly to pass on his evidence, and then enlisted to fight in the French and Indian War, rising to the rank of lieutenant.

He was again taken prisoner, this time by the French, and imprisoned in Quebec. However, the surrounding population was short on provisions and fearful of an uprising by the prisoners of war and so “they thought of sending us away, the most eligible way of keeping themselves from famine, and accordingly put 1500 of us on board a vessel for England.”

Williamson returned to Plymouth in November 1756. Having a damaged left hand from being wounded, he was discharged from the army and given a small gratuity of six shillings. Not enough to return him to Aberdeen, as he set out on the 1000 km walk home, a fact driven home as he arrived, entirely broke, in York.

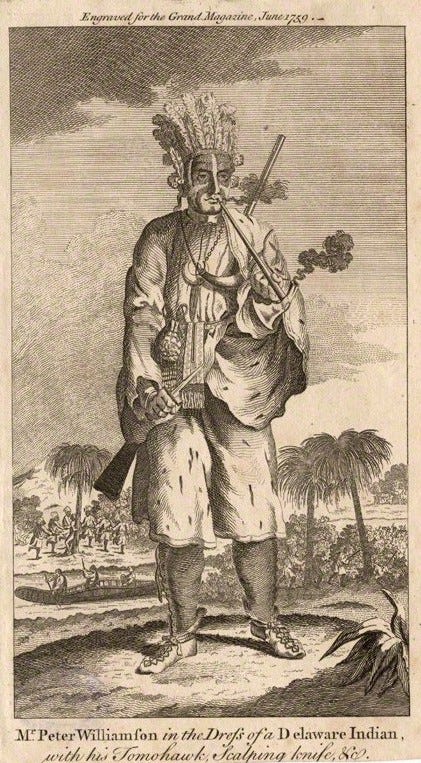

“I was obliged to make my application to the honourable gentlemen of the city of York, who on considering my necessity and reviewing my manuscript on the transaction of the Indians, thought proper to have it printed for my own benefit.” A thousand copies were sold, earning Williamson a tidy £30 profit, and allowing him to finish his journey north, dressing as an Indian and selling books as he went, until In June 1758 he finally returned to Aberdeen.

As he continued to sell his book in his native city, including those lines which implicated the local worthies in his kidnapping, he was charged with libel and brought up before Justices who were, unfortunately for him, the very folk he was accusing. The inevitable guilty verdict saw the surplus copies of his books burned at the city’s Mercat Cross, he was made to sign a statement that he had made false claims, and – final indignity – Peter was banished from Aberdeen as a vagrant.

But Peter was nothing if not a trier. He headed for Edinburgh using what remained of his money to open a coffee shop under Parliament House, which became a favourite gathering place for the city’s legal fraternity. Which brings us to the first of Fergusson’s mentions in The Rising of the Session:

This vacance is a heavy doom

On Indian Peter's coffee-room

For a' his china pigs are toom

Nor do we see

In wine the soukar biskets soom

As light's a flee

Befriended by lawyers, Peter was encouraged to sue the Aberdeen magistrates who had sat in judgement on him and burned his books. He won and was awarded £100 against the Provost of Aberdeen, four bailies and the Dean of Guild.

He then pursued those Aberdeen worthies he believed were complicit in his kidnapping, the case was initially heard at Aberdeen Sheriff court, and – again unsurprisingly – the Doric pillars of respectability were exonerated by their local judge. But Peter’s lawyers appealed to the Court of Session in Edinburgh, Williamson was able to produce evidence, and the Court awarded him £200 damages plus 100 guineas in legal costs – a significant amount of money in those days. Papers connected with his cases remain in the Library of the Faculty of Advocates.

INNOVATOR PETER

With his money, Peter opened a tavern in Parliament Close, and stuck a wooden figure of himself in Indian costume outside as an advertisement. Shy he was not, a marketeer he had certainly become. He opened a printing shop, became a self-taught printer, and invented both a portable printing press and waterproof ink for stamping linen. Not bad progress, but Peter was just getting started.

In 1773 he produced the first Edinburgh Street Directory, linked to his idea of establishing a regular postal service in the city. It is plain the service is up and running 200 years ago as in the 1774 directory it says the publisher (that would be Peter) is willing to dispatch letters and packages up to 3 pounds in weight to locations around the city.

The service ran from his premises every hour on the hour and cost one penny. In 1776 Williamson gave up being an unofficial mail rival to take over the official role as Postmaster, in a penny post system which saw uniformed postmen deliver letters from his printing premises to 17 local shopkeepers spread throughout the city paid to receive letters - the first "post offices". Indian Peter ran this first regular postal service in Scotland for 30 years, before it was integrated into the General Post Office, for which he received the princely sum of £25 for the goodwill of the business and an annual pension of 25 shillings.

Which brings us to Peter’s second appearance in the work of Fergusson, this time in Codicile to Robert Fergusson's Last Will:

To Williamson, and his resetters

Dispersing of the burial letters

That they may pass with little cost

Fleet on the wings of penny-post

Williamson died in 1799, fond of a drink and a tall tale or two till the last. His life continued to fascinate as far away as the United States, where he had spent considerable time and enjoyed his most hair-raising adventures.

In 1878, the Pittsburgh Daily Post carried his story, including details of the final days of his life in Edinburgh:

“Essentially good tempered and of a sanguine disposition, he surrounded himself with many friends among whom he passed not unpleasantly into a hale and hearty old age. It is gratifying to know that he was not unrecompensed for his contrivance of the penny-post. When the institution was ultimately taken under the charge of the government, a pension was bestowed upon Peter Williamson, who was thus satisfactory provided for to the termination of his career.”

It must be said, before we bid adieu to this undoubtedly remarkable character, that some scholars are a little doubtful about parts of his tale, especially his captivity by the Cherokee. Some professional historians are unconvinced, and indeed one who examined his story went so far to describe him as "one of the greatest liars who ever lived.”

He may have stretched the truth, let’s concede. However, that he was a child who became enslaved, then a pioneer in the New World, then a soldier, writer, inventor, innovator, and pioneering businessman is beyond doubt. Most of all, a great survivor. On the rest, who are we to say. And what a life story.