Are wildfires the new normal for Edinburgh and the Lothians?

Blazes are on the rise and our assumptions about 'soggy Scotland' are not helping

The plumes of smoke were visible from miles away; the smell of burning gorse heavy in the air across large parts of the city.

On Sunday, a fire swept across dry gorse on Arthurs Seat - firefighters worked through the night to keep the ever-spreading blaze under control. This is far from the first large wildfire in Edinburgh and the Lothians this year - fire fighters have been called out twice to blazes on Blackford Hill, a forest fire raged for days in West Lothian, and two fields were destroyed in one night in East Lothian.

Catastrophic wildfires in Greece and California have become sadly unsurprising news in recent years. As we sit through another record-breakingly warm and dry Scottish spring and summer, should we be preparing for regular wildfires here? From the perspective of damp, boggy Scotland, it seems ludicrous to be afraid of wildfires - but the risk is real and increasing, and ignorance of it only makes the problem worse.

What does the data say?

According to data from the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service, the total number of fires in Edinburgh and the Lothians has fallen since 2010; but the number of incidents on “grassland, woodland or crops” has increased significantly. The latter are up from an average of 892 per year in 2011-2013, to an average of 1291 per year from 2021-2023 - 45% increase in a decade. Data also suggests that grassland and woodland fires are more common in warm, dry years - during the famously scorching year of 2022, the number of fires in grassland, woodland or crops leapt up to 1682.

In 2025 so far, there have been 188 outdoor fires large enough to qualify as wildfires (1000 square metres); the highest number in 6 years.

While climate change will bring plenty of storm rains to Scotland, our summers are projected to become drier and hotter. One study published by the British Ecological Society estimates that by 2040 the occurrence of extreme drought* in Scotland will have increased from one event every 20 years, to one every 2 or 3; most of these events will happen on the East Coast.

Another factor in the wildfire risk in the Lothians is the soil itself; peat moorland is so flammable that in treeless areas it is dug up to burn in fires. Once peat soil is alight, it can burn underground for long periods - even in moist conditions. The Pentland Hills is a prime example of a dry peat moorland.

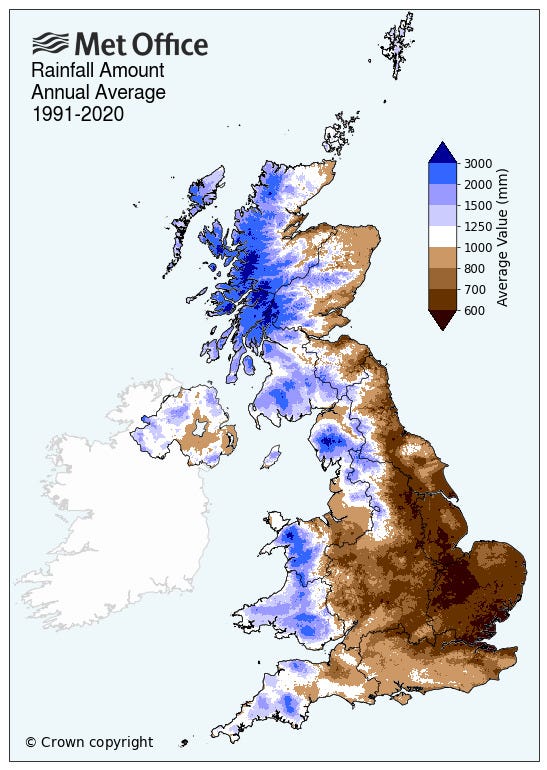

In urban areas, researchers at University College London are now warning of the risk of “fire waves”, where dry urban conditions can lead to multiple fires breaking out at the same time. This is based on research from the summer of 2022 in London, where the fire service had their busiest day since World War II, tackling multiple fires across the city. While average temperatures in London are of course significantly higher than in Edinburgh; the average rainfall is not much higher; at 728mm yearly in Edinburgh, compared to 627mm in London; for context, Glasgow sees 1153mm yearly rainfall.

Thoughts from the front line of wildfire prevention

While climate and environment are making wildfire more likely in Scotland, fires are usually started by another changing factor - human activity. According to SFRS, last weekend’s fire on Arthurs Seat was “almost definitely” started by human activity; although it’s unclear if this was deliberate or accidental.

Area Commander Michael Humphreys, Wildfire Lead, Scottish Fire and Rescue Service, says: “We know that most wildfires in Scotland are started by people and often by accident. While climate change can contribute to longer dry periods and hotter conditions, which in turn can raise wildfire risk, human behaviour remains the single biggest cause.”

Pentland Hills Park Ranger David Allan adds: “It's possible that a piece of broken glass can magnify the sun and spark a wildfire, in theory, but it could just be an irresponsible person with one match.”

During summer months, the Pentland Hills Park Rangers patrol over the regional park from early morning until 10pm. They technically cover other hills such as Blackford, but with only 6 paid staff and a team of volunteers, their resources rarely stretch outside of the Pentlands.

Since the Covid-19 lockdowns, Rangers have started spending an increasing proportion of their time chatting with visitors to make sure they know how to keep themselves and the surroundings safe, aiming to reduce littering, footpath damage, livestock bothering, and dangerous fires.

Often Rangers will have to extinguish campfires which have been set up while extreme fire risk warnings are in place, or in dangerous locations. Sometimes this involves digging deep into the peaty soil which has kept smouldering under the firepit. Often Rangers can nip a fire in the bud before it requires a fire brigade call out - but this means that fire brigade statistics may underrepresent the number of wildfires in Edinburgh and the Lothians.

Allan says that Ranger patrols have been fairly successful this year, but there have been gorse fires in rarely-visited corners of the Pentlands, where the Rangers did not have time to patrol. Fires in the Pentlands have a serious impact on the local wildlife - the area is home to many ground nesting birds; and after one fire near Torphin reservoir Rangers discovered a badger set among the ashes.

The majority of the Pentlands is also managed as farmland - fires pose a risk to the income of these farmers. A recent fire in Musselburgh also destroyed entire fields.

What counts as a dangerous campfire?

The Scottish outdoor access code advises against fires on the ground, and instead recommends using a camping stove or a raised firepit. “If you must have a fire, we will encourage people to go down on the shores of the reservoirs, the risk is minimized there, and the damage,” says Allan. He also advises campers to dig the ground over after the fire has been put out - this helps the grass and other wildlife in the fire spot to recover more quickly.

During periods of very high wild fire risk, SFRS says that any open flames, disposable barbecues and discarded cigarette butts are dangerous.

Allan also advises against collecting firewood from around the area, which prevents the plant matter from feeding back into the ecosystem as it should. He says the intense storms Edinburgh saw over the winter has led to a large amount of wood on the forest floors in the Pentlands. This may create the temptation to build a fire in the woods, or nearby, but Allan says it is important to remember the Pentlands is used by around 600,000 visitors every year. “There could be a perception that you're in the great outdoors, and you can just go out there and cut trees down for your fire. But it's not the Alaskan frontier, it's a small regional park. It gets a lot of visitors. It gets pretty hammered,” says Allan.

Could our own impressions of Scotland be contributing too? “If people are having fires during high wildfire risk, they're just not aware of it, or you have that attitude, it'll be fine, it'll just burn itself out. In our experience, that's not the case,” says Allan. UCL researchers say a key aim of their fire wave research is to help raise public awareness of fire risk in the UK, and to prevent fires caused by irresponsible behaviour. I have been guilty of scoffing at “extreme wildfire risk” signs as I shiver in 16 degrees with wind chill. But we may have to accept that Scotland is not always the green, slightly boggy, haven we have grown up with.

The bottom line: leave no trace

Everything points to wild fires being an increasingly common part of life in Edinburgh and the Lothians, as our climate changes and warm dry summers become increasingly common. However, the number of fires we will see will be much lower if public perception catches up with the environmental reality; we can’t keep using our green spaces the way we have in the past.

On a national scale, SFRS is investing £1.6 million in all-terrain vehicles, trailers, specialist equipment and PPE, alongside the creation of 14 wildfire tactical advisor roles, to address the increasing risk of wildfires. But simple behaviour changes like using camping stoves and raised firepits, bringing our own firewood and paying attention to wildfire risk warnings will also make a huge difference to wildfire risk. And as Allan says, this all fits into the age-old golden rule for outdoor access in Scotland: leave no trace.

* Extreme drought is defined according to the globally recognised Standardised Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index.