A very human hill: how we shaped Arthur’s Seat and its surroundings over six millenia

Taking a walk through the history of our most famous natural landmark

“If I were to choose a spot from which the rising or setting sun could be seen to the greatest possible advantage, it would be that wild path winding around the foot of the high belt of semi-circular rock, called Salisbury Crags”

Sir Walter Scott in Heart of Midlothian.

Edinburgh is uniquely blessed with its hills; havens of green space, excellent viewpoints. Holyrood Park in particular is an enormous expanse of nature in the heart of the city.

While its craggy, gorse-clad form seems deliciously wild to us, Arthur’s Seat has in fact been moulded by human activity for millennia. Everything, from the grassy hilltops, to the waterways, to the shape of Salisbury Crags themselves, has changed, thanks to us.

Stone and Iron age: from wood to farmland

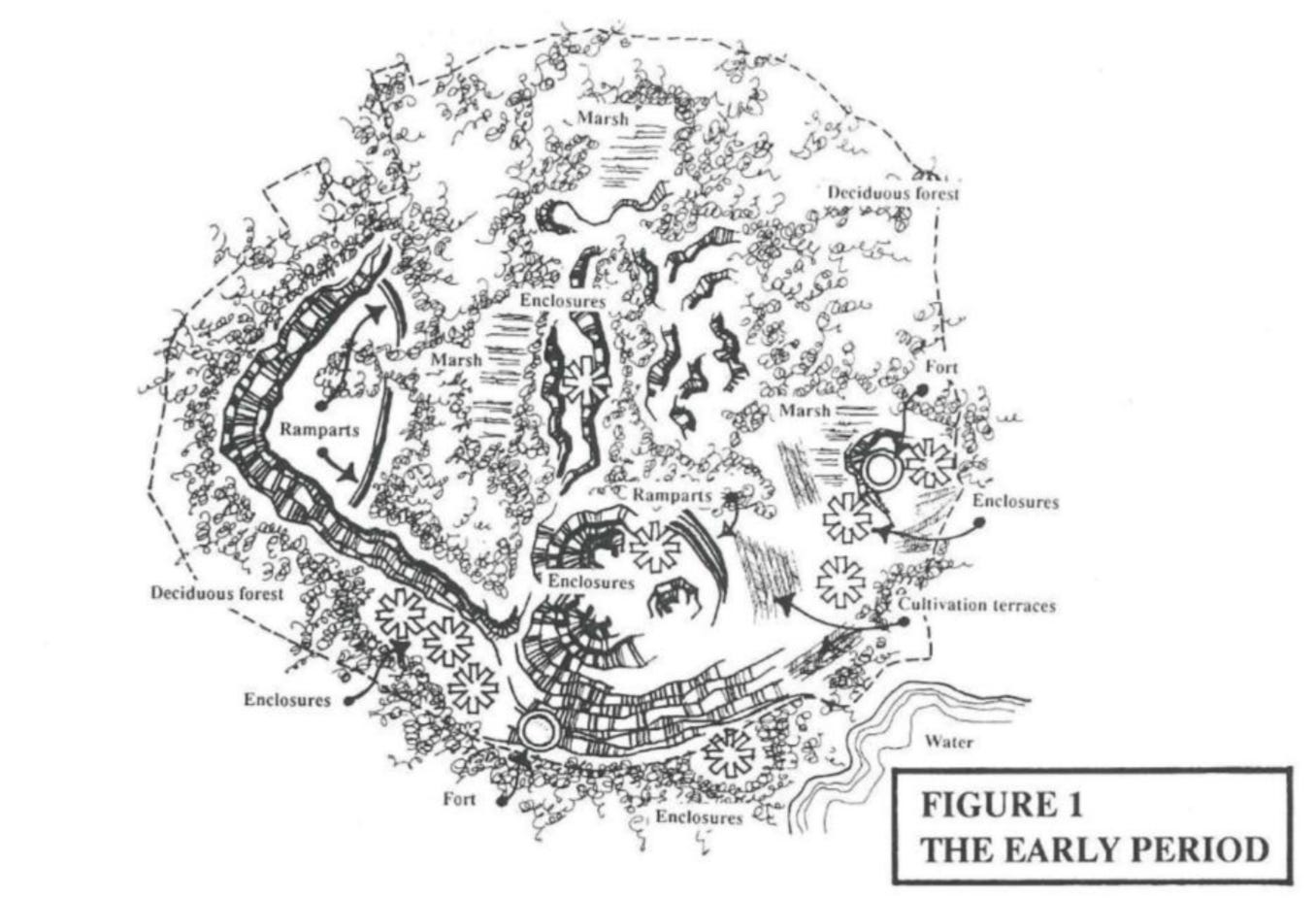

The geological form of Arthur’s Seat and the Crags was created 340 million years ago when the volcano erupted for the last time. During the Stone Age, pre-4000 BC, the hill and its surroundings looked completely different to now. Used sometimes by hunter-gatherers, it was covered in woodland; trees like birch, willow, alder, hazel and oak would have covered its slopes.

In the Bronze Age, people began living on the hill; farming and houses transformed the wooded landscape into something more similar to the open grassland we see today, although with more bog and no lochs apart from Duddingston. Terraces which were cut into the side of the hill for agriculture at this time can still be seen when the light’s right.

Just south of the hill in Duddingston Loch, the largest hoard of iron age items in Scotland was unearthed. The collection of human bones, animal horns, spearheads, swords, and even a bucket handle has been a marvellous source of mystery since it was unearthed in the late 18th century. Why were all of the weapons bent or broken?

With the Iron Age came fortresses; the remains of four forts lie under the earth on Salisbury Crags, Dunsapie Crag, Samson’s Rib and Arthur’s Seat. The most visible is on Dunsapie Crag, where the remains of buildings can be seen on the surface.

Medieval period

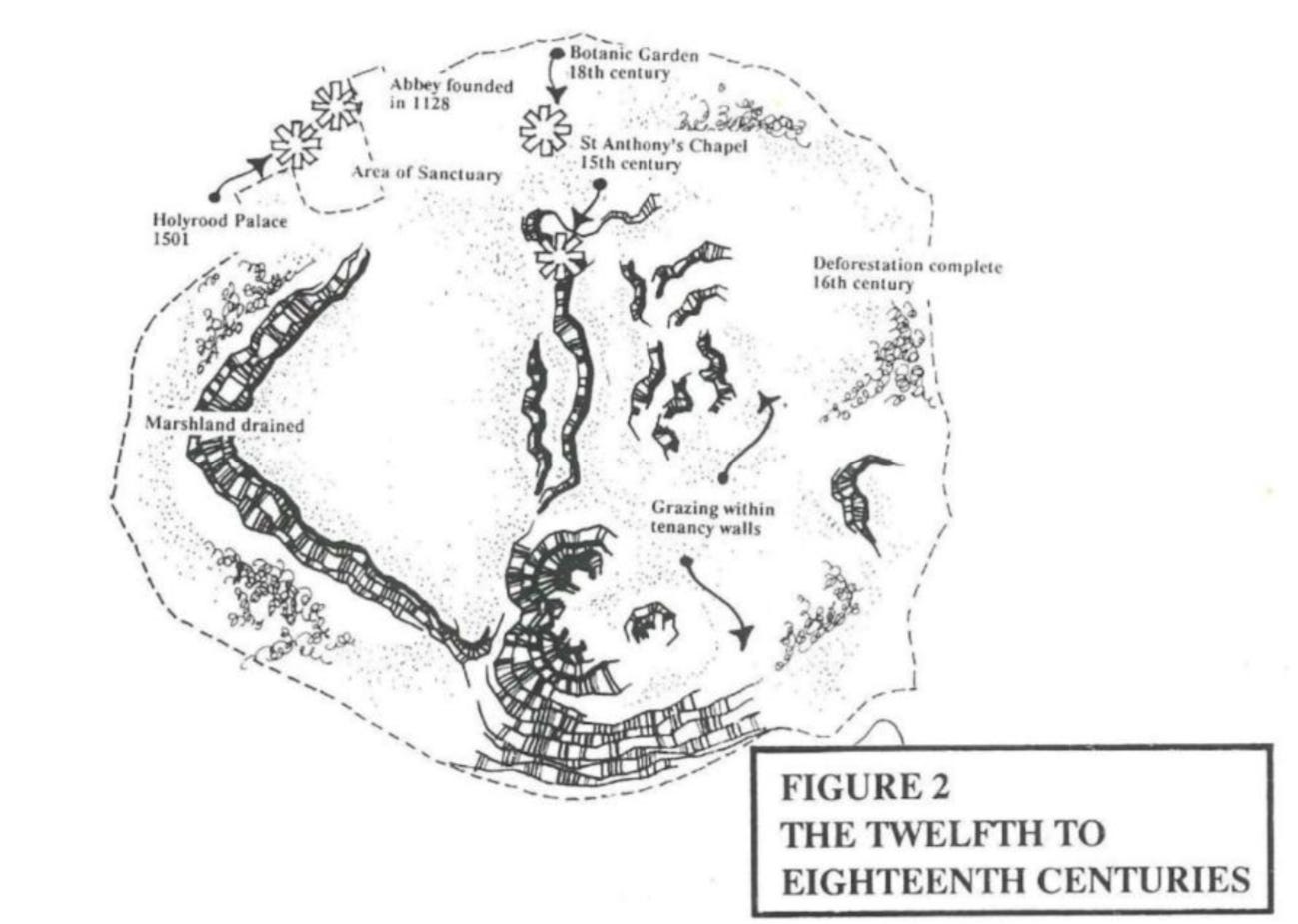

From the 12th to 16th century, the area roughly equating to Holyrood Park was managed by the abbeys at Holyrood and Kelso. Farming on the hill would have provided a modest income for the abbeys, and also meant the hill remained treeless. You might have occasionally spotted a royal out using the hill as a hunting ground, too.

It was also during this time that the iconic St. Anthony’s Chapel, and the path leading from Holyrood Abbey to the hillside kirk, were constructed. There is little known about when or why St Anthony’s Chapel was built; some believe it was a beacon to pilgrims coming to the Abbey by boat, others think it might have been a way of keeping pilgrims out of the way of the monks and their daily business.

16th - 18th century

It was in the 16th century the hill gained its name “Arthur’s Seat,” rather than the previous “Craggenmarf’, from the Gaelic Crag nan Marbh, ‘Dead Men’s Crag’. The first recorded use of the name is from the Flyting of Dunbar and Kennedie, a staged comedy between two noblemen in King James VI’s royal court. Nobody knows how the name Arthur’s Seat emerged. It could be an anglicisation of a gaelic name such as “Àrd-na-saighead , (height of arrows) or Ard-thir Suidhe (Place on High Ground). It might also be linked to the fact that the hill is one of the many places in the UK rumoured to be the site of Camelot and King Arthur.

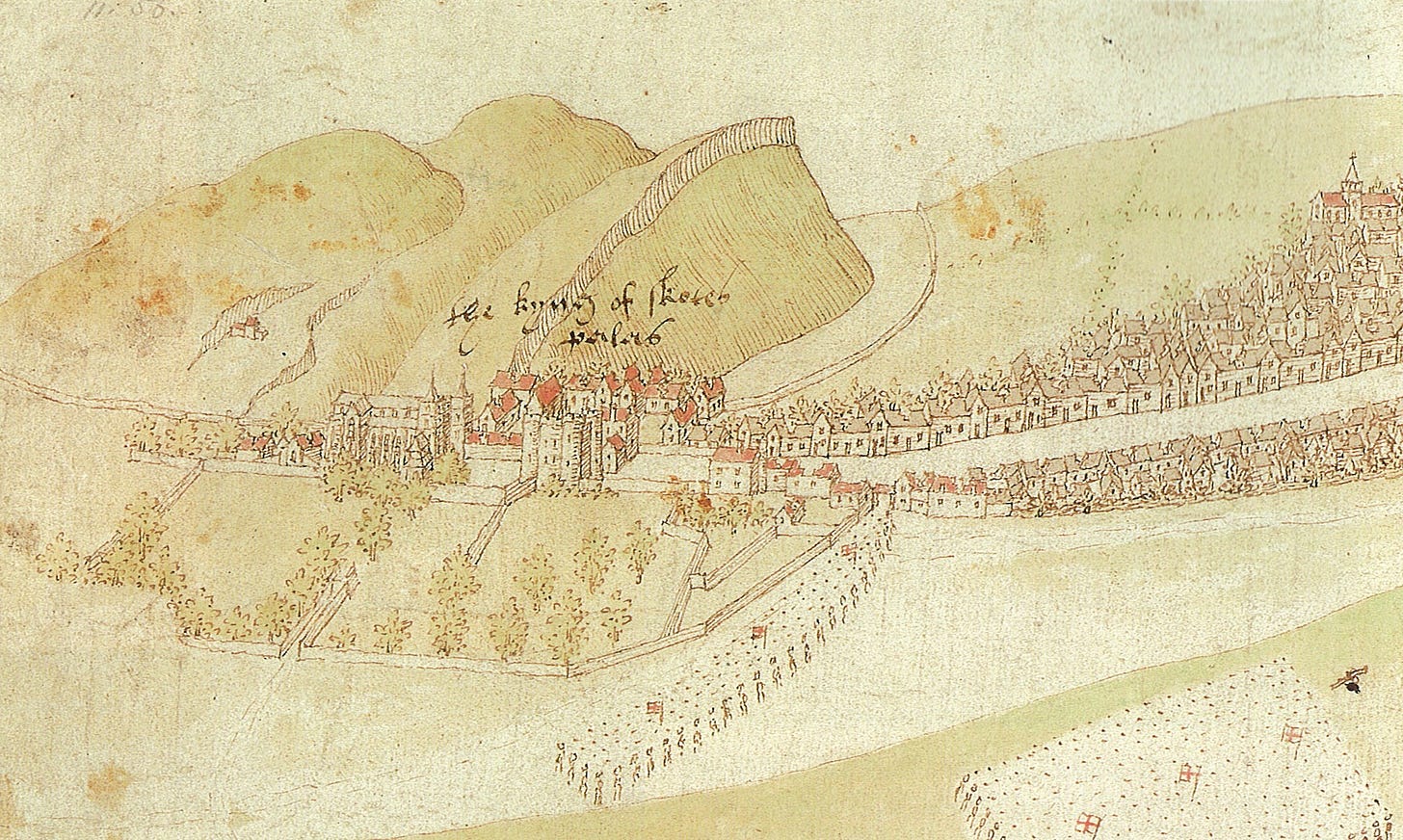

In the 1540s, the park was enclosed by King James V; most of the 8km long boundary wall survives to this day. It is likely that stone from a quarry on the North-east slopes of Salisbury Crags was used for this wall, as well as for building the Palace of Holyrood House. The park was well-used by the following royals; in 1564, Mary Queen of Scots ordered a dam to be constructed across Hunter’s Bog, between the Crags and Arthur’s Seat, to create a loch where a naval battle was re-enacted. The remnants of this dam are still visible today; but the changes brought to the park over these three centuries were minute compared to what was to come in the Victorian era.

19th century: development and “mutilation”

Quarrying on Salisbury Crags continued at a fairly low intensity until the 19th century. At this point, quarrying along the cliff face itself became so intensive that in 1825 the Scotsman lamented over the “mutilated honours of Salisbury Crags.” Edinburgh citizens ended up taking quarrying companies to court over the damage to the Crags; the case lasted twelve years, and reached the House of Lords, but eventually brought an end to quarrying in Holyrood Park, and brought the Park back into Royal ownership.

As an official Royal Park, and once again open to the public, Holyrood Park was significantly developed for recreational use. In 1820 the Radical Road had been constructed, partially inspired by Sir Walter Scott’s writing about the path. In the 1840s and 50s, thanks to Prince Albert himself taking a keen interest in the park, the construction of Queen’s Drive, along with several grand entrance gates, and the draining of bogs to create two artificial lochs (Dunsapie Loch and St. Margaret’s Loch) solidified this area for the first time as a space dedicated to leisure. St. Margaret’s Loch was used for boating, skating and curling during this time. The old South Quarry, which cut rock directly from the face of the Crags, became a popular rock-climbing location during the sport’s infancy.

An ever-changing hill

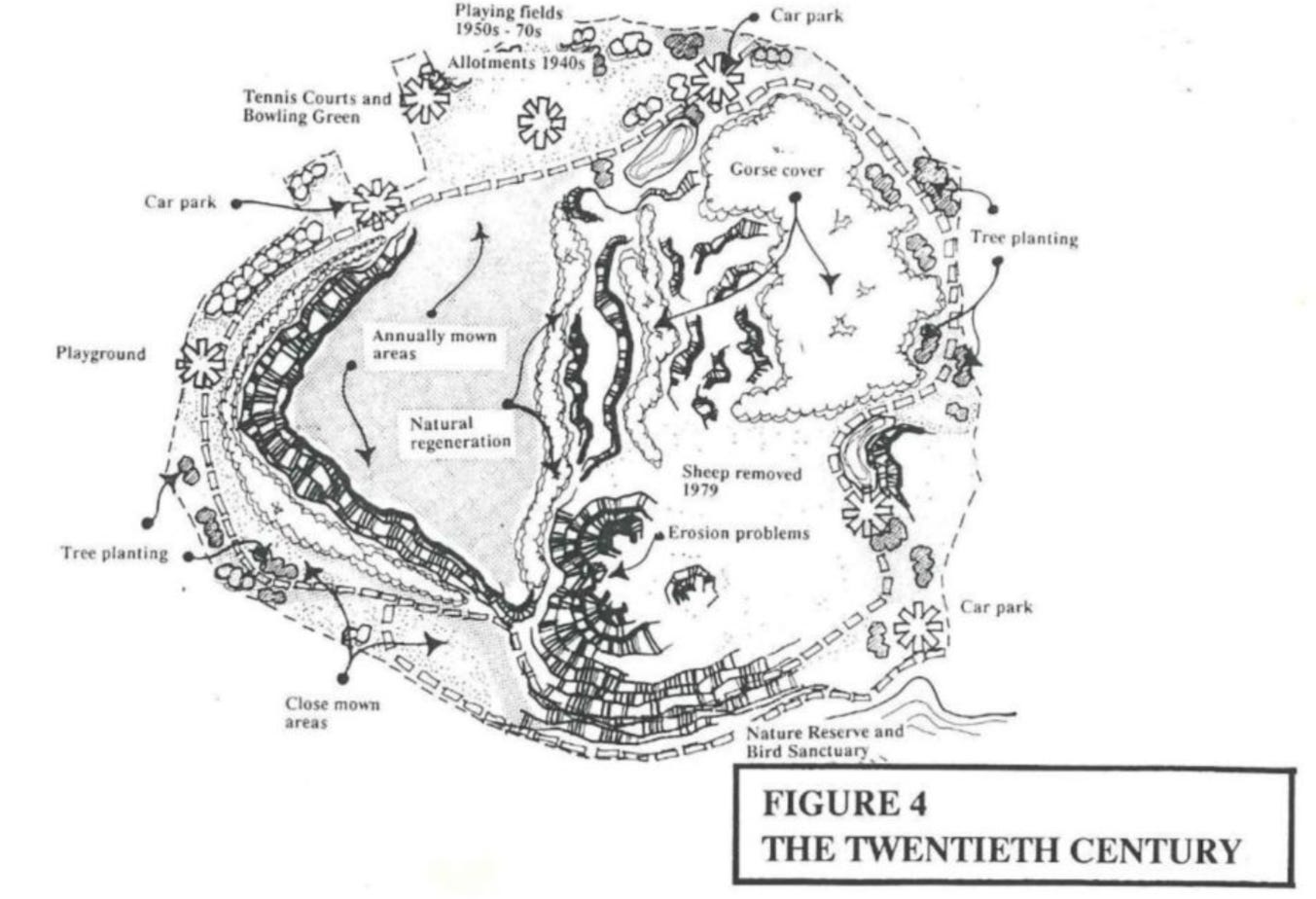

By the turn of the 20th century, the roads, lochs, crags and grasslands of Holyrood Park looked much like they do today. The trees which line the park were planted during the post-war period, thousands of years after humans began clearing trees from the site.

It was only in 1977 that grazing on Arthur’s Seat ended. At this time there were 800 sheep on the hill during summer months, and they provided an excellent grass-cutting service. They were taken off due to concerns about over-grazing and worries about car traffic and dogs bothering the sheep. It is only since their removal that gorse has spread so far across the sides of the hill.

Recent years have also been a keen reminder that the rock-face of Arthur’s Seat and Salisbury Crags is never static; the Crags shed fifty tonnes of its face in 2018, leading to the closure of Radical Road. Duddingston Road South remains closed due to a rockfall from the other iconic cliff face, Samson’s Rib.

We have a tendency, as humans, to believe that what we grew up with is “natural.” And yet, for better or worse, the natural world around us is forever evolving, often in response to our human influence. Arthur’s Seat will continue to be moulded by the politics of Scotland and of Edinburgh, perhaps not by quarrying companies or fortress-builders, but certainly by conservationists and tourists, not to mention all those Edinburgh runners and dog walkers. I wonder what it will look like in the next century.