40 years on: how the miners' strike reshaped Midlothian

The violence and victimisation that accompanied Thatcher's breaking of the unions

It set friend against friend. Fathers against sons. It was the Battle in Britain, a less-than-civil war fought against attempts to kill not just an industry, but communities and their way of life.

The Miners’ strike in 1984 lasted a year and remains an issue that brings out strong emotions in people who lived through it. Bilston Glen in Midlothian became the focal point in Scotland as striking miners picketed to prevent those breaking the strike from entering the pit.

Bilston Glen was a super-pit. Opened in the 1950s, it produced more than a million tons of coal a year at its peak when it employed almost 2500 people. There is nothing left to mark the huge mine that once stood there.

The strike was, for many, the defining moment in an era as far removed from today’s “beige” politics as can be imagined. An ideologically-driven Prime Minister in Margaret Thatcher up against an equally ideologically-driven union leader in Arthur Scargill. Both believed utterly they were right, even when they were wrong.

Much has been said during its 40th anniversary about the way in which the UK Government conducted the strike, and that is as it should be. Declassified papers have clearly shown the UK Government of the day misinformed the miners and the public about their plans for the industry and kept secret their high level of involvement in the management and conduct of events around the strike, even going so far as to undermine advanced peace talks between the National Coal Board and the union.

The way in which many miners were treated by the National Coal Board because of the strike earned the contempt of many – among them local police officers, dismayed at miners sacked and blacklisted for the slightest of offences, or no offence at all.

THE ENEMY WITHIN

Proving divisive and inflammatory political speeches are nothing new, forty years ago, in a speech at the Carlton Club in London, Mrs Thatcher described the miners as “the enemy within” and a danger to liberty.

Contrast that with former Tory Prime Minister Harold McMillan who, in his maiden speech to the House of Lords that year, described the same striking miners as “the best men in the world, who beat the Kaiser’s and Hitler’s armies and never gave in”. The “terrible strike” was “pointless”, he added. He received a standing ovation.

David Hamilton was most certainly one of “the enemy within.” The NUM pit delegate at Monktonhall colliery, near Musselburgh, and the regional strike committee chairman, he vividly recalls the impact of Mrs Thatcher’s speech.

“For the younger guys it just seemed another attempt to attack us, our characters, another stick to try to beat us with. A provocative thing to say about folk who’d never done anything wrong. But for the older guys, some of whom had served in the forces in the war or had worked down the pit to help the war effort, it was a terrible and unforgivable thing to say and they took it hard.”

These days he’s Sir David Hamilton, former MP for Midlothian. He was talking to me after a special afternoon at Dalkeith Miners’ Club at Woodburn, marking the 40th anniversary of the Miners’ strike of 1984-85. It went well, with 400+ turning up to join old workmates and friends.

“Ach, it was a good day. We all saw people we hadn’t seen for 30 years or even more. We had a good laugh together, but you know the best thing, David? There was no bitterness. Hurt, yes, at what happened, but no bitterness. Most of them were old colleagues but others also joined us. Charlie Reid from The Proclaimers came along, he helped in the strike HQ when he was just a lad.

“I met one guy who’d worked with me at Moktonhall who’d flown up from Wales for the day, and said ‘I wouldn’t have missed this for anything’.

“There were plenty of laughs, and quite a few tears. Especially when we had a toast to absent friends. We’ve lost a few across the years and we know another event like this might never happen.”

David Hamilton played a prominent role in the strike in the Lothians and I remember meeting him in the same miners’ club in 1984. I asked for an interview, to chat with him and other members of the committee. He agreed – then told me with a grin that they would only talk if I got the beers in. I happily stood my round.

The strike brought some incredibly difficult times for the mining communities. Entitlement to benefit changes brought in by the Government meant the miners were deprived even of money for food, and soup kitchens had to be established. Starving strikers into submission appeared a legitimate tactic in late 20th century Britain.

This caused widespread distress. In one particularly upsetting incident, one Bilston Glen miner took drastic action to draw attention to the plight of the miners, nailing himself to the floor of his Dalkeith home. He refused treatment until he could speak to the NUM’s Scottish Area President, Michael McGahey, who was revered by the men.

OVERCOME AND HUMBLED

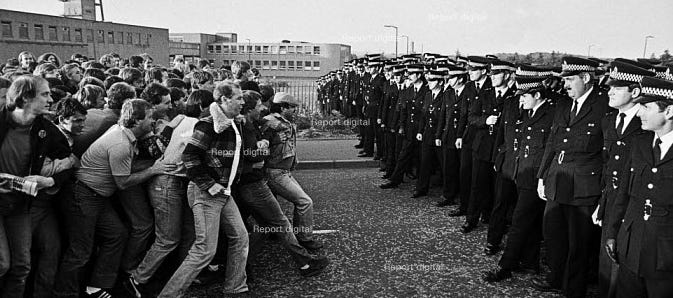

On the picket line anger and tension often filled the air like a gathering thunderstorm. Tough men in hardhats faced tough men in uniforms. That sustained violence on the scale experienced in the north of England did not happen was thanks to the efforts of the local strike committee and the police.

There were inspiring moments too. Local companies rallied to support families they regarded as customers, sure, but also as friends and neighbours. I remember reporting on a bakery firm in Prestonpans sending trays of morning rolls and Scotch pies to the strikers on a daily basis for months on end. “These folk have been loyal customers for our business for years” they told me, “and now it’s our turn to show the same.”

Or consider this testimony from an unnamed police officer to a Scottish Government Review into the impact of the strike: “Both my sons were invited to, and attended, the Christmas Party in the Miners’ Welfare Institute and received their share of confectionery sent by French miners to their counterparts in the village. My wife was overcome and humbled by the fact that people who were literally struggling for their very survival could even think about her children, let alone involve them.

“My wife was so touched by this that she contributed home-made soup to the strike kitchen on a regular basis.”

Black humour was ever present. David Hamilton recalled the strikers receiving a stock of cold soft drinks from a local business, delivered directly to the picket line at Bilston Glen. “The police shoved us right down the road, past where the drinks were stored, and then promptly helped themselves. They were laughing at us as they drank our drinks.

“We met that night and the boys decided to get our own back. We had another delivery, and this time the lads doctored it – a little pee in each bottle - and the next day we allowed the cops to push us back down the road. It was us laughing as they helped themselves that day. If only we’d had smart phones and social media in those days.”

TARGETED AND VICTIMISED

David Hamilton was also one of the disproportionately high number of Scottish miners who were victimised due to the strike. At the start, the NCB said it would sack picketing miners convicted of criminal offences. Around 1,400 miners were arrested during the strike in Scotland, with more than 500 convicted.

David spent nine weeks on remand in Saughton Prison awaiting trial on an assault charge following an argument with a “strike-breaker” in Woodburn Miners’ Welfare Club in the early autumn of 1984. He was refused bail. When his case came to trial in Edinburgh Sheriff Court on 20 December the jury took all of 25 minutes to accept his defence that he had been defending himself, and find him not guilty.

Nonetheless he was sacked by the NCB. He won an industrial tribunal, but the NCB refused reinstatement. He was out of work for some time.

Jackie Aitchison was the NUM delegate at Bilston Glen. He was sacked after an infamous incident when the local NCB management painted white lines outside the colliery and warned that pickets who crossed them would be sacked. Jackie crossed the line and was sacked. He never regained his job, despite winning his tribunal case.

In Scotland, miners were twice as likely to be sacked as their colleagues in England were, at nearly 14 per thousand. In Midlothian, the number was almost doubled again, at nearly 25 per thousand. Yet in Scotland, charges brought were generally minor breaches of the peace or obstruction. A high proportion of those sacked were union officials.

PARDONED BUT NOT COMPENSATED

“There is no doubt in my mind that we were targeted from the start. It damaged a lot of good people who had done nothing wrong, nothing illegal. 36 men from Bilston Glen and 46 from Monktonhall – 106 from throughout the Lothians – were never allowed to go back to work” David said.

Alex Bennett was another NUM official targeted, the branch chairman at Bilston Glen: “I was blacklisted. I couldn’t get a job for three years,” he later told reporters. “I’m 74 at my next birthday and I’ve never even had a parking ticket.” Being pardoned, he said, would “right a wrong”.

Alex was a campaigner not just for a pardon, which was granted in 2022 to those convicted of minor breach of the peace and obstruction offences, but also for compensation. He too won his industrial tribunal. Had he been made redundant, he would have been owed £27,000. He left with nothing. Alex died in 2023.

The independent Review into the Impact of the Miners’ Strike of 1984-85 set up by the Scottish Government a few years ago took evidence from many of those involved on all sides. It made just one recommendation – to pardon those convicted of specific, lesser strike-related offences. In his report, John Scott KC remarked the running down of the coal industry had been handled with care and consideration over decades.

“In contrast, in the 1980s, deindustrialisation was managed recklessly by the UK Government, setting aside the interests of manual workers and the voice of their union representatives.”

He went on to criticise the way in which miners were treated. “Importantly, for many the greatest loss still felt was that of their respectability… For proud, respectable, working men, the loss of their good name through having a criminal conviction was a continuing pain which they cannot remove. We heard of some who, until the day they died, remained acutely conscious of what they felt was this loss of respectability.”

Tom Wood was a Chief Inspector in Lothian and Borders Police, one of the senior officers regularly on duty at Bilston Glen, who would go on to become Deputy Chief Constable of the force.

He remains saddened that a wedge was driven between police and the mining community but insists that throughout, despite the suspicions of miners, the force remained fiercely independent of any political or outside interference. Lothian was not an area that sent for reinforcements from down south, with Chief Constable William Sutherland determined the local situation should be policed by local officers.

“No horses, dogs or batons were ever deployed at Bilston Glen. Generally, it was a pushing-shoving kind of affair. It only ever escalated when there were flying pickets present, usually from the north of England. That was when it deteriorated, and people need to remember that many officers were also injured on the line.

“From the start there was a lot of sympathy among police officers for the miners. It’s a big mining area. Many of our people had friends and relatives in the picket lines. You had brothers on opposite sides, but we had sworn an oath to uphold the law and protect their right to peacefully picket and the right of other miners to work, if they chose to. It was a difficult time.”

‘SPITEFUL AND EXCESSIVE’

“The miners thought we were in cahoots with the NCB. I can tell you we were not, and played no part in passing on any information to them. Sadly all the NCB needed to do was keep an eye on the court public records. The extra-judicial punishments meted out to these men by their employers were clearly spiteful and excessive. But for me the real lesson from the miners’ strike was not about what happened on the picket line but what did not happen afterwards. The failure to invest in new jobs and training in many mining communities condemned them to decades of despair and decay.”

Tom remembers meeting regularly with the union leadership. “I know David well. He was always a decent, pragmatic guy.” Tom recounted that the Flotterstone murders - when a serving soldier shot and killed three colleagues in an army payroll robbery in the Pentlands and went on the run - happened in the middle of the strike and stretched resources.

“We spoke with strike leaders in our area. They immediately agreed to halt picketing to allow us to deal with the murder and apprehend the guy.”

David also remembers the incident well. “We agreed straight away, it was the right thing to do. What they had to do dealing with the murders was important.”

After his own spell of unemployment, David worked for several years in the public sector, then served as a councillor for six years, before becoming the county’s MP in 2001, following the retirement of Eric Clarke.

Early in his time as MP he was invited to visit the Lothian and Borders Police divisional HQ at Dalkeith Police Station, where an enthusiastic young Chief Inspector showed him around the facility. They were accompanied by an older Sergeant. At one point in the visit, the Chief Inspector offered a personal tour of the building “including the cells”.

David said: “The sergeant couldn’t contain himself any longer. He looked at me, I looked at him, and he couldn’t stop laughing. The Chief Inspector was perplexed, and eventually the Sergeant managed to tell him ‘I think you’ll find Mr Hamilton has seen the cells before, sir.’ I had to laugh as well. I don’t think the Chief Inspector knew what to think.”

The “enemy within” stood down as an MP in 2015 and was knighted for services to politics and public life a year later.